The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated existing global gender inequities that impact the accessibility of immunizations to women and children worldwide, influencing their access to health services, education, and economic opportunities. Gender-related inequities contribute to barriers to immunization for people of all genders. Although girls and boys in most settings are equally likely to be vaccinated, evidence has found that advancing global gender equity can play an important role in ensuring all children have access to vital health resources such as immunization.

Key Points

- Gender inequality can prevent people of either gender from accessing critical health resources such as vaccination for themselves and their children.

- Higher levels of gender inequality for women are correlated with higher child mortality and lower childhood immunization rates.

- The more empowered women are – i.e. have control over family decision-making, financial resources, and safe travel/transportation – the more likely their children are to be vaccinated.

- Maternal education is significantly associated with immunization coverage for children and a child’s immunization status has been found to predict greater educational attainment.

- At the national level, higher levels of gender inequality are associated with higher rates of zero-dose status for children (children who received no doses of the DTP vaccine).

Immunization interventions will only succeed in expanding coverage and widening reach when gender roles, norms and relations are understood, analysed and systematically accounted for as part of immunization service planning and delivery.”

Why Gender Matters: Immunization Agenda 2030

Global research has found that gender equality, “the absence of discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender” 1, can be closely linked to health outcomes across populations. Evidence from around the globe finds that “reducing gender inequality could improve health outcomes at a population scale, resulting in increased overall and healthy life expectancy and decreasing years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disease burden, in the general population, and in men as well as women.” 2

What is Gender Equity?

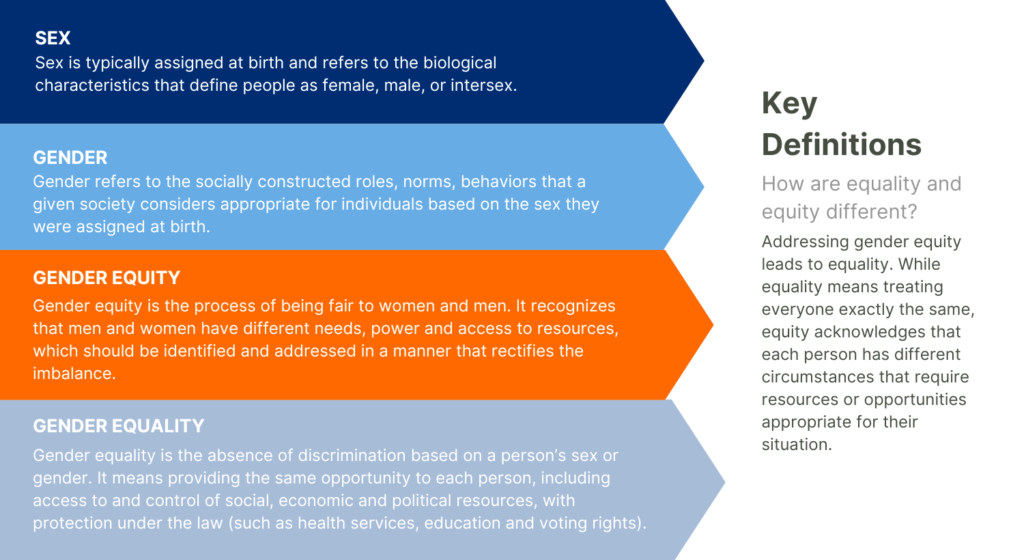

Sex is typically characterized as either male or female and refers to the biological attributes that a person is born with. Gender refers to the socially constructed roles, norms, and behaviors that a given society considers appropriate for individuals based on the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender also shapes the relationships between and within groups of women and men1. Gender inequality can prevent people of either gender from accessing critical health resources such as vaccination for themselves and their children. However, because gender-related barriers are underpinned by power relations that extend across individuals to systemic levels, women and girls are often especially vulnerable to these inequalities.

A recent World Health Organization report on gender and immunization defines gender equity as “The process of being fair to women and men. It recognizes that men and women have different needs, power, and access to resources, which should be identified and addressed in a manner that rectifies the imbalance. Addressing gender equity leads to equality.” 1

The goal of gender equity is for people of all genders to have fair access to critical resources for themselves and their families. While equality means treating everyone exactly the same, equity acknowledges that each person has different circumstances that require resources or opportunities appropriate for their situation. Gender equity involves recognizing and rectifying the gender-based differences that exist, especially those related to needs, access, and control over resources.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated existing global gender inequities that impact the accessibility of immunizations to women and children worldwide, influencing their access to health services, education, and economic opportunities. For example, data collected from 193 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that women were 1.21 times more likely than men to report ceasing their education for reasons other than school closures.3 Additionally, between March 2020 and September 2021, 26.0% of women reported employment loss compared to 20.4% of their male counterparts.3

Gender Equity and Immunization

Although girls and boys in most low- and middle-income settings are equally likely to be vaccinated, evidence has found that advancing global gender equity can play an important role in ensuring all children have access to vital health resources such as immunization.1

Several global studies have found associations between broad gender inequality and childhood immunization rates. A 2017 study examined the country-level factors influencing vaccination coverage in 45 low- and lower-middle income Gavi-supported countries, finding that countries with the least gender equality–as measured by factors such as reproductive health, women-held parliamentary seats, and educational attainment–also had lower rates of vaccine coverage. 4

How Gender-Related Barriers Impact Immunization Uptake

An increased effort to address existing gender barriers is necessary to achieve universal coverage in child immunization.5 Evidence suggests that increasing gender equality and empowering women have the potential to improve global childhood vaccination rates.

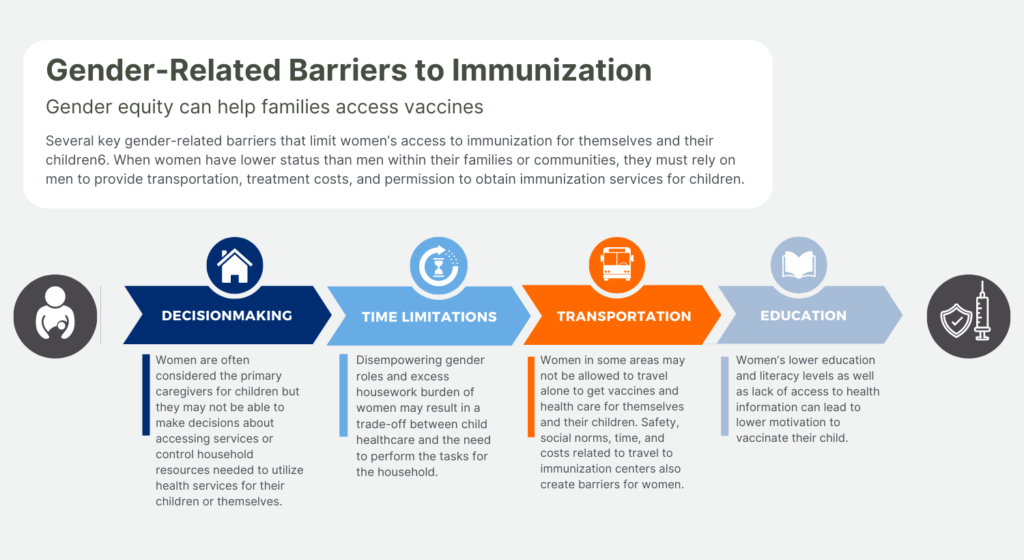

A 2018 discussion paper on immunization and gender barriers from the Equity Reference Group for Immunization identified several key gender-related barriers that limit women’s access to immunization for themselves and their children6. When women have lower status than men within their families or communities, they must rely on men to provide transportation, treatment costs, and permission to obtain immunization services for children.1,6

Several studies have shown that maternal education is significantly associated with immunization coverage for women and their children. Women with limited literacy or those with poor education are less likely to understand vaccination cards and may not know that multiple visits are required for some vaccination4. An analysis of immunization equity in 45 Gavi-eligible countries concluded that “children of the most educated mothers are 1.45 times more likely to have received DTP3 than children of the least educated mothers.” 4

Gender Equity Can Improve Immunization Rates

Evidence indicates that empowering women and increasing gender equality increases the chance that mothers will immunize their children. Across various settings and countries, the association between gender inequality and higher levels of under-immunized children persists.

- A 2016 systematic review assessed women’s agency and vaccine completion among children under 5 in low-income countries. Largely, decision-making was positively associated with the odds of complete childhood immunization. The review found that in lower-income settings, “specific dimensions of women’s agency may enhance vaccination coverage for children, and that empowering women in such settings shows promise as a means to improve child health.” 7

- A 2017 review of Gavi-supported countries found that countries with higher levels of gender inequality had lower and less equitable levels of child vaccination coverage.4

Immunization Can Foster Gender Equality

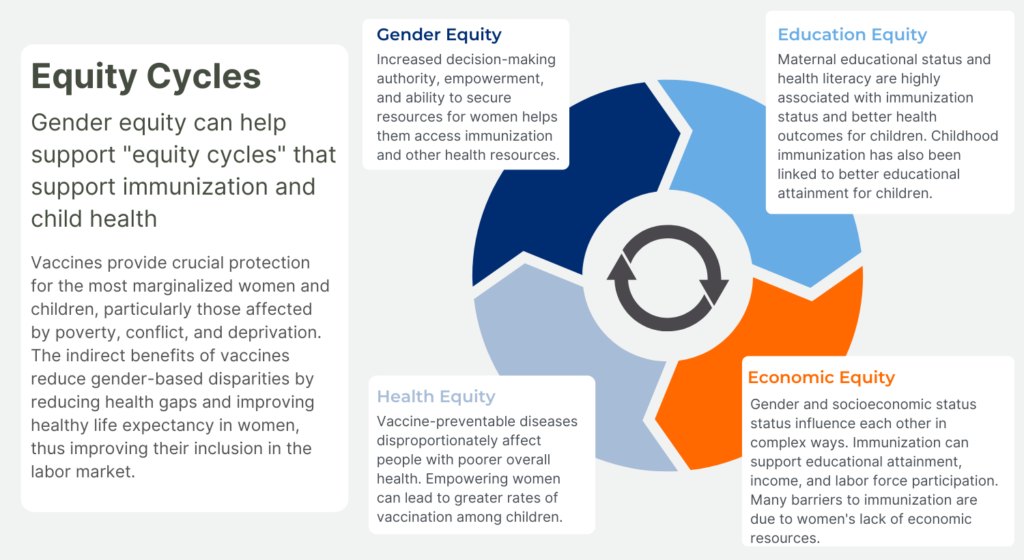

Vaccines provide crucial protection for the most marginalized women and children, particularly those affected by poverty, conflict, and deprivation. The indirect benefits of vaccines reduce gender-based disparities by reducing health gaps and improving healthy life expectancy in women, thus improving their inclusion in the labor market8. This modeling study suggests that by preventing illnesses, childhood vaccination can lead to higher educational attainment and labor participation for women, resulting in reductions in socioeconomic gender disparities8.

- A 2020 modeling case study8 found that HPV vaccination among girls can narrow socioeconomic gender disparities by reducing the cervical cancer burden of women. One model estimates that HPV vaccination can prevent up to 80% of cervical cancer cases and deaths. A 5% improvement in health from HPV vaccination was estimated to result in a 5.9% increase in female labor force participation.

- A large study in India9 demonstrated that childhood immunization was associated with improvements in adult schooling attainment in India by as much as 10%. This could lead to a higher income for women, as a woman’s wage in India is estimated to increase by 5-8% for each extra year of schooling.

Gender and Zero-Dose Status

Gender inequity also contributes to “zero-dose” status, which refers to children who have not received a single dose of DTP-containing vaccines10. Countries with higher gender inequity have been found to also have a greater prevalence of zero-dose children than countries with lower gender inequity5. With the spotlight on COVID-19, the 2022 WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC) show that 112 countries experienced stagnant or declining DTP3 coverage since 2019, with 62 countries declining by at least 5 percentage points11,12. Globally, an estimated 18 million children have not received a single vaccine12.

The pandemic has not only disrupted routine immunization worldwide, but has also had alarming direct and indirect consequences on progress toward Sustainable Development Goals related to gender equity and child health.

- Children of mothers with high levels of social independence (a measure of indicators of a woman’s ability to achieve her goals) were found to be 8.3% less likely to be zero-dose than children of women with low independence.13

- A study representing 165 countries between 2010–2019 found that on average, greater gender equality was associated with markedly better coverage for DTP3 immunization5. Countries with higher gender inequality (as measured by gender-based advantage or disadvantage in health, education, and control over economic resources) had higher zero-dose prevalence (10% vs. 3%) and lower DTP3 immunization coverage (81% vs. 94%) compared to countries with lower measures of gender inequality.

- An analysis of DHS data from 50 countries14 (representing 74% of low-income, 40% of lower-middle, and 11% of upper-middle-income countries in the world) found that “children born to less empowered women are over three times more likely to belong to the zero-dose category compared to those born to women with a high level of empowerment.”

There is a Strong Association Between Maternal Education and Child Health

Across contexts, research consistently finds that mothers with more education are also more likely to have their children immunized. There is also evidence that women’s education has a “dispersion” or “spillover” effect on child health that can benefit communities more broadly.15

- A systematic review and meta-analysis found a 31% reduction in under-5 all-cause mortality for children born to mothers with 12 years of education. One additional year of maternal schooling was associated with a 3% reduction in under-5 mortality.16

- Women who are health literate—irrespective of their education levels—are more likely to vaccinate their children, in both rural and urban settings. A study of 1,170 women from 60 Indian villages found that a mother’s health literacy level was positively associated with children’s receipt of DPT3 vaccination after adjustment for confounding17.

- An analysis of Nigerian DHS data collected in 2014 revealed that a mother’s education level influences the likelihood of their child being immunized. Furthermore, the average education level of women within a community was found to have a protective effect on children beyond the benefits of their own mother’s schooling that may lead to better opportunities. This dispersion of benefits may be associated with women’s capacity to take advantage of better access to power and resources that having an education can support.18

Solutions: Immunization as an Equity Catalyst

The Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) emphasizes the importance of immunization as a catalyst for advancing gender equality by addressing gender-related barriers. To reach the goal of leaving no one behind, gender-related barriers need to be effectively addressed from both the demand- and supply-side by all stakeholders6,19. Special attention should be paid to setting and context when attempting to implement gender-responsive approaches to immunization.1

Improve the quality, accessibility, and availability of services

- All people should be treated with dignity and should be provided with the knowledge to make informed decisions.

- Immunization services should be close to areas where hard-to-reach populations frequently visit and should be bundled together with other health services.

Integrate services and collaborate across sectors while working with change agents

- To overcome barriers, relationships should be established with organizations beyond the health sector, especially with grassroots organizations and community-based groups.

- Immunization programs should empower change agents and civil society with the skills to voice their views.

Apply a gender lens to research and innovation by investing in gender data and analysis

- Action must be informed by data. To best identify and respond to gender inequities, data should be sex-disaggregated and informed by a gender analysis.

Globally, there is a lack of data regarding the needs and experiences of gender-diverse and gender non-conforming people and barriers to immunization. The barriers to health services that gender-diverse people face are important and specific efforts should be made to collect data and include gender-diverse people in research.1,20

References

- World Health Organization. Why Gender Matters: Immunization Agenda 2030. World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033948

- Veas C, Crispi F, Cuadrado C. Association between gender inequality and population-level health outcomes: Panel data analysis of organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101051. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101051

- Flor LS, Friedman J, Spencer CN, et al. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: a comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021. The Lancet. 2022;399(10344):2381-2397. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00008-3

- Arsenault C, Johri M, Nandi A, Mendoza Rodríguez JM, Hansen PM, Harper S. Country-level predictors of vaccination coverage and inequalities in Gavi-supported countries. Vaccine. 2017;35(18):2479-2488. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.029

- Vidal Fuertes C, Johns NE, Goodman TS, Heidari S, Munro J, Hosseinpoor AR. The Association between Childhood Immunization and Gender Inequality: A Multi-Country Ecological Analysis of Zero-Dose DTP Prevalence and DTP3 Immunization Coverage. Vaccines. 2022;10(7):1032. doi:10.3390/vaccines10071032

- Feletto M, Sharkey A, Rowley E, Gurley N, Sinha A. A Gender Lens to Advance Equity in Immunization. Equity Reference Group for Immunisation; 2018. https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/document/programmatic-policies/ERG_A-gender-lens-to-advance-equity-in-immunization.pdf

- Thorpe S, VanderEnde K, Peters C, Bardin L, Yount KM. The Influence of Women’s Empowerment on Child Immunization Coverage in Low, Lower-Middle, and Upper-Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):172-186. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1817-8

- Portnoy A, Clark S, Ozawa S, Jit M. The impact of vaccination on gender equity: conceptual framework and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine case study. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1090-3

- Nandi A, Kumar S, Shet A, Bloom DE, Laxminarayan R. Childhood vaccinations and adult schooling attainment: Long-term evidence from India’s Universal Immunization Programme. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2020;250:112885. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112885

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Zero-dose children and missed communities. Published November 4, 2021. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/strategy/phase-5-2021-2025/equity-goal/zero-dose-children-missed-communities

- UNICEF. Vaccination and Immunization Statistics. UNICEF Data. Published July 2022. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/immunization/

- UNICEF. COVID-19 pandemic leads to major backsliding on childhood vaccinations, new WHO, UNICEF data shows. Published July 15, 2021. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-pandemic-leads-major-backsliding-childhood-vaccinations-new-who-unicef-data

- Johns NE, Santos TM, Arroyave L, et al. Gender-Related Inequality in Childhood Immunization Coverage: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of DTP3 Coverage and Zero-Dose DTP Prevalence in 52 Countries Using the SWPER Global Index. Vaccines. 2022;10(7):988. doi:10.3390/vaccines10070988

- Wendt A, Santos TM, Cata-Preta BO, et al. Children of more empowered women are less likely to be left without vaccination in low- and middle-income countries: A global analysis of 50 DHS surveys. J Glob Health. 12:04022. doi:10.7189/jogh.12.04022

- Feletto M, Sharkey A. The influence of gender on immunisation: using an ecological framework to examine intersecting inequities and pathways to change. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001711. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001711

- Balaj M, York HW, Sripada K, et al. Parental education and inequalities in child mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2021;398(10300):608-620. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00534-1

- Johri M, Subramanian SV, Sylvestre MP, et al. Association between maternal health literacy and child vaccination in India: a cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(9):849-857. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-205436

- Burroway R, Hargrove A. Education is the antidote: Individual- and community-level effects of maternal education on child immunizations in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2018;213:63-71. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.036

- USAID MOMENTUM. Now Is the Time to Recognize and Reduce Gender-Related Barriers to Immunization. USAID MOMENTUM. Published July 15, 2021. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://usaidmomentum.org/now-is-the-time-to-recognize-and-reduce-gender-related-barriers-to-immunization/

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The struggle of trans and gender-diverse persons. OHCHR. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/ie-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity/struggle-trans-and-gender-diverse-persons