December 12th is recognized worldwide as Universal Health Coverage (UHC) day. Universal health coverage “ensures all people, everywhere, can get the quality health services they need without financial hardship.” Equity is at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goal target 3.8, which seeks to achieve universal health coverage and financial risk protection for all. Immunization equity helps ensure that all children, regardless of where they live, have the opportunity to live a full, healthy life.

Key Points:

- As of 2020, 17.1 million children are categorized as zero-dose, defined as never having received a single dose of life-saving DTP vaccine.

- The number of children at risk due to zero-dose status or under-vaccination has increased according to 2020 reports.

- Zero-dose children not only lack access to vaccines but lack access to other essential child health services.

- As the most widely available health intervention in the world, childhood immunization can be leveraged to strengthen primary health care for missed communities, bringing us closer to UHC.

What Does Zero-Dose Mean?

As of 2020, an estimated 17.1 million children did not receive the first dose of Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis vaccine (DTP1) – an increase of 3.5 million children from 20191. An estimated 80% of these zero-dose children live in Gavi-eligible countries1.

The term zero-dose refers to children who have not received a single dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (DTP1). These zero-dose children are often concentrated among the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, including the lowest-income households. Zero-dose status can help act as a proxy indicator of access to immunization and health services access more generally: When young children aren’t protected against some of the most lethal infectious diseases it indicates they and their families may be missing out on additional basic services, like antenatal care or schooling2.

- The global number of zero-dose children fell by nearly 75% between 1980 and 2019, from 56.8 million to 14.5 million3.

- By 2019, global coverage of the third dose of DTP (DTP3) was estimated at 81.6% globally – more than double from 1980 DTP3 coverage estimates of 39.9%3.

- Over the past decade, global vaccine coverage has plateaued beneath global coverage goals. Since 2010, 94 countries and territories recorded decreasing DTP3 coverage3.

Where are Zero-Dose Children Located?

Over the last 20 years, national governments and international health organizations have made tremendous progress in ensuring that all children have access to a safe, and healthy start to life. By focusing on zero-dose children, we concentrate resources on the populations who compounded deprivation where access to resources is the most challenging for families:

- Nearly 50% of zero-dose children live in three key geographic contexts: urban areas, remote communities, and populations in conflict settings4.

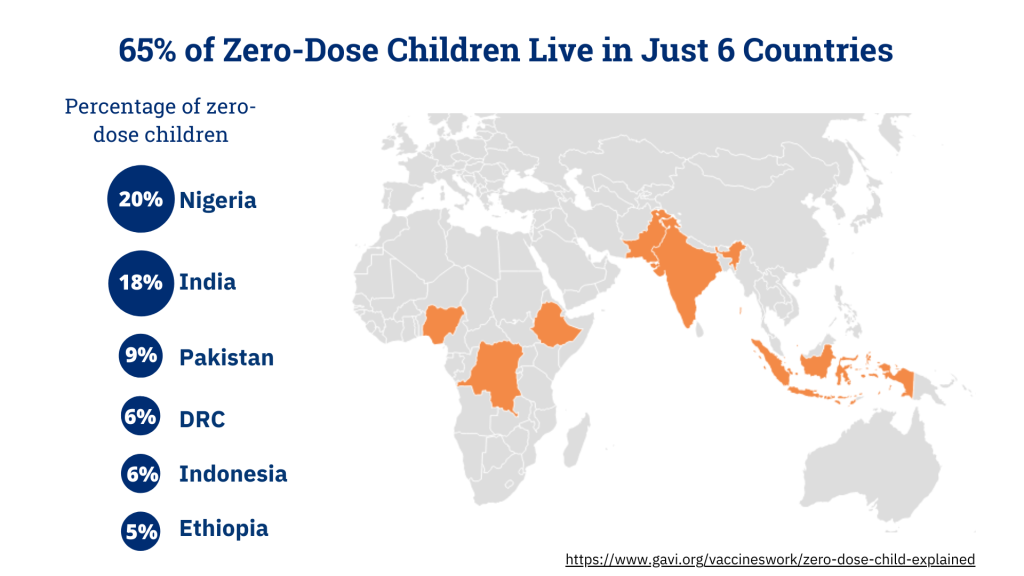

- Six Gavi-supported countries are home to 65% of zero-dose children: Nigeria (20 percent), India (18 percent), Pakistan (9 percent), the DRC (6 percent), Indonesia (6 percent), and Ethiopia (5 percent)4.

- Communities with many zero-dose children also tend to have girls who are not in school; women with limited agency; high rates of violence against women; and lack of contraceptive, reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and pediatric health services2.

- These missed communities are often the epicenters of disease outbreaks (e.g., yellow fever, measles, meningitis, cholera, Ebola virus disease) and can thus be valuable targets for prevention efforts2.

Immunization: Investing in Health Systems for All

When children are “zero-dose” this lack of vaccine access often indicates a dire lack of access to other key health services for communities. Unvaccinated children disproportionately live in households with limited access to other primary health care services, and routine vaccination services may provide the opportunity to bring caregivers into contact with the health system5.

- When a child misses out on basic vaccines, they are also likely to be missing out on other essential health interventions. This also means that their families and communities are most likely to be missing out on basic health services like maternal and neonatal care, access to sexual and reproductive health services nutritional supplements, and malaria prevention6.

- Mothers of zero dose children are twice as likely to miss out on antenatal care or skilled birth attendance and these families are less likely to have access to clean water or sanitation4.

- Children from families without access to primary health care services – such as institutional delivery, antenatal care, and maternal vaccination – also tend to be less likely to be vaccinated5.

Deprivation, Missed Communities, and Poverty

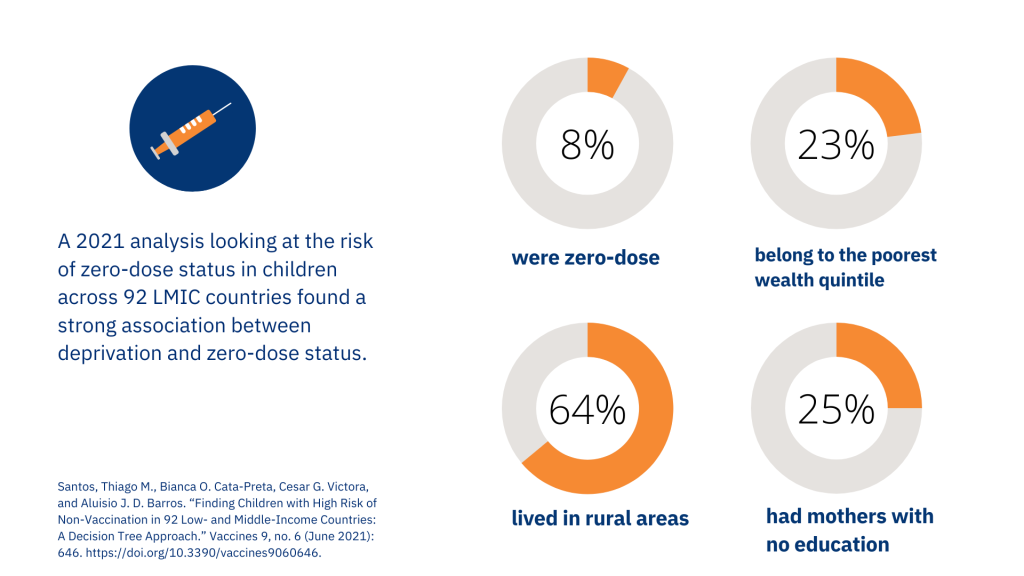

A 2021 analysis7 looking at the risk of zero-dose status across 92 LMIC countries found a strong association between deprivation and zero-dose status: The most deprived group represented children who were not born in a health facility, to a mother who did not receive a tetanus vaccine before or during pregnancy and reported no antenatal care visits. The group characterized as the most deprived had the highest prevalence of zero-dose children (42%).

- Two-thirds of zero-dose children live in households surviving below the international poverty line ($1.90 per day)2,7.

- Among the highest risk group, 47% were in the poorest wealth quintile, 89% lived in a rural area, and 81% had mothers with no education7.

- There are large inequalities in drop-out rates, with drop-out being twice as high for children from the poorest households, with a DPT1 to MCV drop-out rate of 18% compared to 9% in wealthier households8.

Gender Equity, Women’s Empowerment, and Zero-Dose Status

In many social contexts, women and mothers are primary caregivers for children and hold an important role in children’s immunization. Women’s empowerment relates to having the autonomy, agency and ability to make informed decisions, including seeking care and health services for children. Several studies have found that women’s empowerment can be associated with higher immunization coverage and better child health for children.

- A 2022 analysis of standardized national house-hold surveys from 50 countries supports the importance of gender equity and women’s empowerment for child vaccination, especially in countries with weaker routine immunization programs. When data from all 50 countries was pooled, the analysis found that children from mothers in the low levels of social independence had 3.3 times higher prevalence of zero-dose status compared to mothers in the high levels of social independence group9. Assuming that this association is causal, these results show that “there would be 4.7 million fewer no-DPT children in the world if all of them had empowered mothers.”

- Additionally, research from 2020 has also found routine childhood vaccination is associated with increased educational attainment and earnings for women. Women born after India’s Universal Immunization Program (UIP) rollout attained 0.29 more schooling grades compared to women from the same household born before UIP rollout10. Among unmarried women, the UIP was associated with an increment of 1.2 schooling years, which corresponds to as much as an INR 35 (US $0.60) increase in daily wages. Thus, the researchers concluded that the UIP is also likely to improve the economic status of women in India.

- In a 2017 analysis of immunization coverage in 45 low- and lower-middle income Gavi-eligible countries, researchers found that overall, maternal and paternal education were two of the most significant drivers of coverage inequities in these countries11. Pooling the data from all countries, the authors found that “children of the most educated mothers are 1.45 times more likely to have received DTP3 than children of the least educated mothers.”

- In a 2011 study in India, the children of mothers who participated in an empowerment program were significantly more likely to be vaccinated against DTP, measles, and tuberculosis than children of mothers not involved in the program12. This study also spillover effects: In villages where the program occurred, children of mothers not in the program (non-participants) were 9 to 32% more likely to be immunized against measles than in villages where the program did not occur (controls). Overall, measles vaccine coverage was nearly 25% higher in the program villages compared to the control villages.

New Efforts are Needed to Reach Every Child

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health services and preventive interventions, including childhood immunizations, and new efforts are critically needed to ensure no one is left behind. Reaching zero-dose children and missed communities with health services like routine immunization is a key goal of UHC as well as Immunization Agenda 2030 and the Gavi Alliance’s 2021–2025 Strategy.

“Health for all means reaching those left furthest behind with live-saving vaccines as a pathway to providing other health services,” Gavi CEO Seth Berkley said in an International UHC Day video message from leaders around the world. “As countries roll-out COVID-19 vaccines we have a historic opportunity to strengthen routine immunization, to reach zero-dose and missed communities with a full course of vaccines, along with primary healthcare services and build resilience to future shocks.”

References

- Muhoza P. Routine Vaccination Coverage — Worldwide, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7043a1

- Forum on Microbial Threats, Board on Global Health, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Critical Public Health Value of Vaccines: Tackling Issues of Access and Hesitancy: Proceedings of a Workshop. National Academies Press; 2021:26134. doi:10.17226/26134

- Galles NC, Liu PY, Updike RL, et al. Measuring routine childhood vaccination coverage in 204 countries and territories, 1980–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020, Release 1. The Lancet. 2021;398(10299):503-521. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00984-3

- Gavi. The Zero-Dose Child: Explained. Published April 26, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/zero-dose-child-explained

- Santos TM, Cata-Preta BO, Mengistu T, Victora CG, Hogan DR, Barros AJD. Assessing the overlap between immunisation and other essential health interventions in 92 low- and middle-income countries using household surveys: opportunities for expanding immunisation and primary health care. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;42:101196. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101196

- Gupta A. Opinion: Reach “zero-dose” children to build back better. Devex. Published July 6, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-reach-zero-dose-children-to-build-back-better-100292

- Santos TM, Cata-Preta BO, Victora CG, Barros AJD. Finding children with high risk of non-vaccination in 92 lowand middle-income countries: A decision tree approach. Vaccines. 2021;9(6). doi:10.3390/vaccines9060646

- Cata-Preta BO, Santos TM, Mengistu T, Hogan DR, Barros AJD, Victora CG. Zero-dose children and the immunisation cascade: Understanding immunisation pathways in low and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2021;39(32):4564-4570. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.072

- Wendt A, Santos TM, Cata-Preta BO, et al. Children of more empowered women are less likely to be left without vaccination in low- and middle-income countries: A global analysis of 50 DHS surveys. J Glob Health. 2022;12:04022. doi:10.7189/jogh.12.04022

- Nandi A, Kumar S, Shet A, Bloom DE, Laxminarayan R. Childhood vaccinations and adult schooling attainment: Long-term evidence from India’s Universal Immunization Programme. Soc Sci Med. 2020;250:112885. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112885

- Arsenault C, Harper S, Nandi A, Mendoza Rodríguez JM, Hansen PM, Johri M. Monitoring equity in vaccination coverage: A systematic analysis of demographic and health surveys from 45 Gavi-supported countries. Vaccine. 2017;35(6):951-959. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.041

- Janssens W. Externalities in Program Evaluation: The Impact of a Women’s Empowerment Program on Immunization. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2011;9(6):1082-1113. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01041.x