From Abuja to Atlanta, recent infectious disease outbreaks have all too commonly captured the regular news headlines. In this Featured Issue on vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, the VoICE team goes past the headline, down to the fine print. We bring you an evidence-backed overview of vaccine-preventable infectious disease outbreaks worldwide, with a special focus on the circumstances that increase the likelihood of an outbreak, the less-obvious health and economic consequences, and a “top five” list for outbreak prevention and preparedness.

A selection of VoICE evidence in this issue

Key Messages

- Infectious disease outbreaks can happen anywhere and have significant, and often hidden, social, health and economic repercussions.

- A large proportion of recent infectious disease outbreaks are of vaccine-preventable diseases.

- The likelihood or severity of an outbreak is increased by factors such as low vaccination coverage, crowding, poor sanitation, malnutrition, and human mobility.

- Outbreak prevention and preparedness needs to be systematically integrated into health systems and specific areas must urgently be strengthened to include immunized healthcare workers, streamlined health communications, and ready surveillance systems.

Introduction

Disease outbreaks happen in nearly every corner of the globe – from the remote Amazon to Amsterdam. An analysis of a World Health Organization (WHO) epidemics database found that from 2005-2014, nearly 400 outbreaks of infectious disease (not including measles) were reported to the WHO. Nearly 40% of these outbreaks were due to vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) – with yellow fever, polio, meningococcal disease and cholera accounting for 9/10 of the outbreaks due to VPDs. The proportion of outbreaks caused by VPDs was as high as 70% in the African region. The ubiquity of disease outbreaks globally speaks to the range of complex factors that contribute to outbreaks of various infectious diseases, but there are some combinations of factors that can easily ignite an outbreak of epidemic proportions.

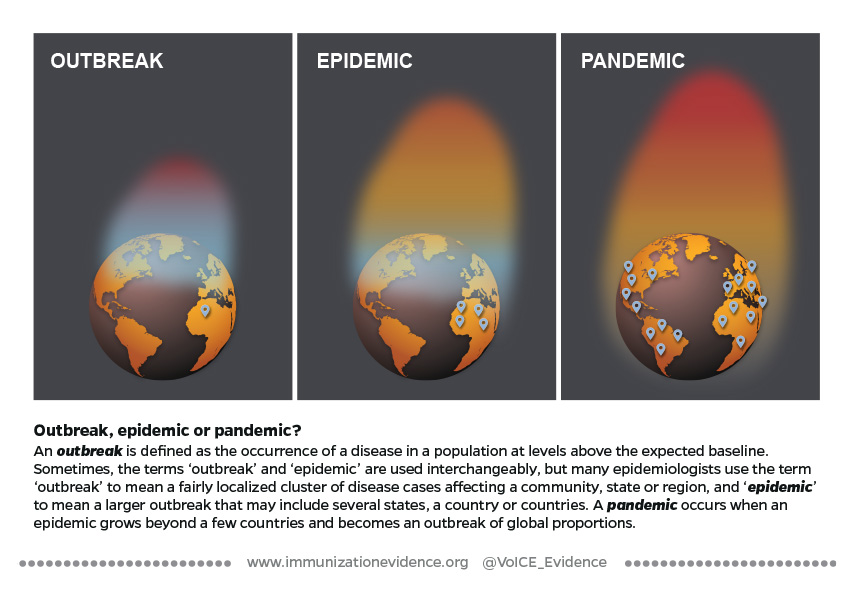

Outbreak, epidemic, or pandemic?

A Fire Waiting to Happen:

Circumstances that increase the risk of outbreaks

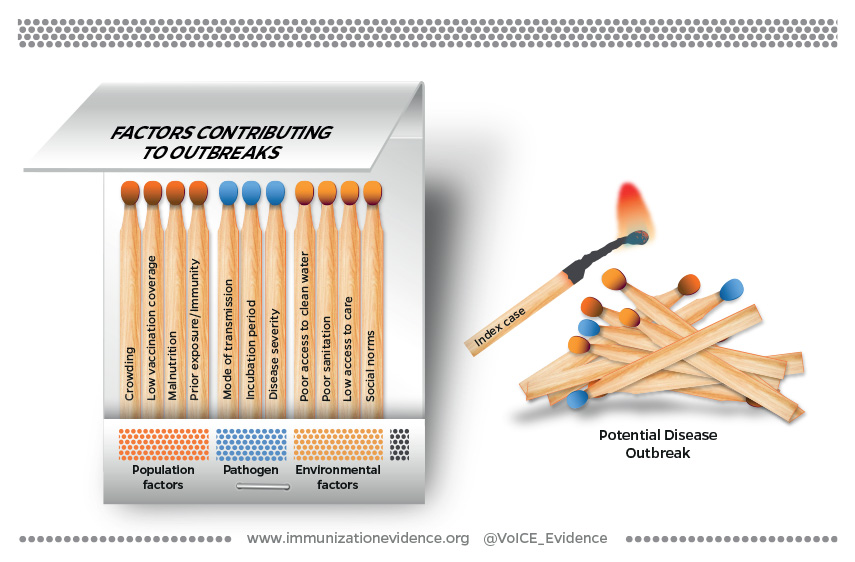

There are a triad of elements that influence the likelihood and severity of an infectious disease outbreak. These include factors related to:

- The Pathogen – aspects of the disease agent itself (virus or bacteria), such as how it is transmitted from person to person, how contagious it is, the incubation period before symptoms appear, how severe the infection may be and how likely it is to result in death.

- The Population – factors affecting the state of health of the population at risk, including the proportion vaccinated, malnourished or living in sub-optimal conditions such as overcrowding, and how people move on small or large spatial scales.

- The Environment – generally refers to environmental factors that affect the spread of disease such as access to clean water and sanitation, access to health care, social norms and cultural practices – for example in the case of Ebola where traditional burial practices bring people into contact with infected bodily fluids which transmit the virus.

Figure 1: Pathogen, population, and environmental factors can ignite an outbreak of infectious disease.

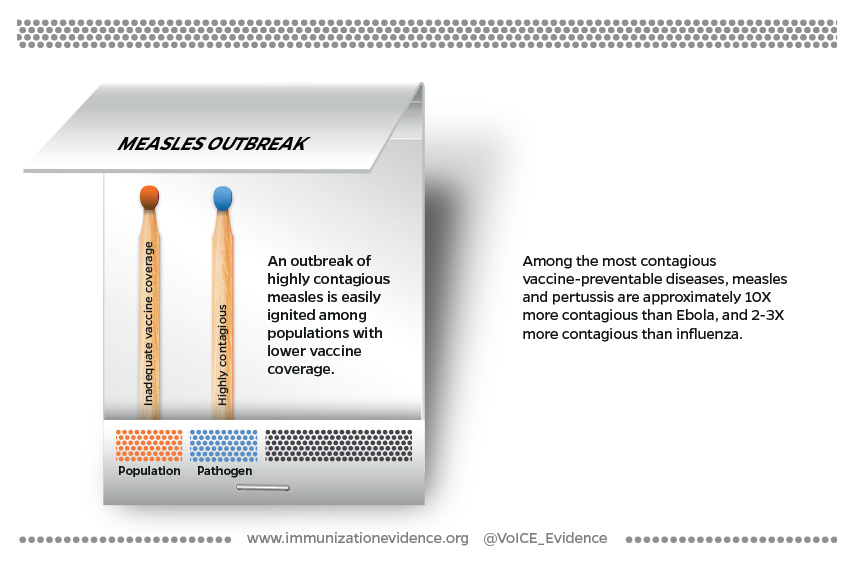

An outbreak can ignite when sparked by only a handful of the factors described above, such as in the case of measles or pertussis – two highly contagious pathogens which can rapidly take advantage of gaps in vaccine coverage. In other circumstances, parts of all three elements – pathogen, population and environment – are present and create the perfect conditions to kindle an outbreak.

Cracks in the immunization firewall

A high firewall of immunization coverage with very very few gaps is required to protect populations from outbreaks of highly transmissible and contagious infections, such as measles or pertussis, which have the potential to spread rapidly and far. An infection like measles is so contagious that almost all susceptible people who are exposed will become infected meaning that about 95% of a community needs to be protected to stop measles virus transmission. Add to that the fact that contagiousness occurs before the telltale rash (and very often before anyone knows what is causing the illness), and you can see how just those two pathogen-related factors cause some outbreaks to explode. In a community with lower than 95% vaccine coverage, the exposure of a single person without immunity to the virus is the single spark that is needed to start an outbreak that quickly burns through a community of people who have little or no immunity. The connection between measles and low vaccination coverage is so strong that some researchers describe measles outbreaks as being a “canary in a coalmine” that brings to light programmatic weaknesses in immunization coverage in places where data on vaccination coverage is thin or unreliable.

Figure 2: Factors contributing to measles outbreaks.

The firewall for a disease like Ebola must be just as strong but for different reasons. Ebola is not very contagious when compared to other infections, but has an exceedingly high risk of death – up to 70% with some strains. (An animated visualization from the Washington Post of the relative contagiousness and mortality risk of different diseases.) When and exactly where the disease will appear is impossible to predict (see “The case of Ebola, a zoonotic infection”, below) and a vaccine against the disease has not yet been approved. For these reasons, outbreak control measures for Ebola, including significant efforts to find people who have been exposed, must be swift and widespread. An experimental vaccine for Ebola is being used in a “ring” vaccination strategy to vaccinate everyone who has come in contact with someone who has the disease, and has proven to be nearly 100% effective in preventing infection, if administered soon enough after exposure. Gaps in this vaccination ring mean the deadly disease has the potential to continue spreading.

Complex emergencies

Global socio-political events, including armed conflicts and other complex humanitarian emergencies, can result in a highly flammable set of circumstances – a “box of matches” containing nearly every population and environmental factor, which can easily spark a significant outbreak. In a study of the overlap between complex humanitarian emergencies and disease outbreaks, researchers found that more than 40% of complex emergencies that occurred between 2005-2014 were associated with an outbreak of infectious disease, with a high likelihood that the outbreak was vaccine-preventable.

The mass migration of people that often results from complex humanitarian emergencies can set off a “risk factor cascade”, that includes decreasing vaccination coverage, undernourishment, overcrowding, and poor sanitation, dramatically increasing the risk of an outbreak with each added cascade factor.

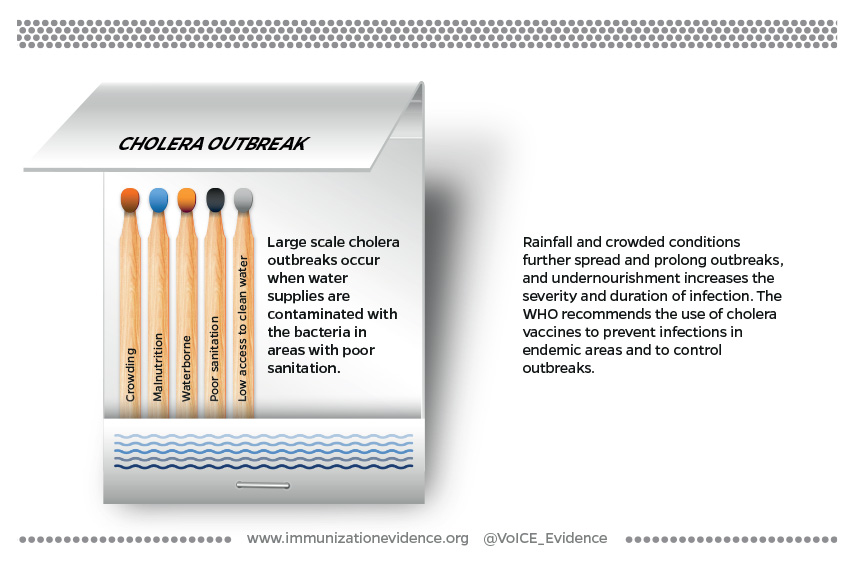

When environmental conditions are poor and pathogen-related factors are significant, only a tiny spark is required to ignite an outbreak, as is often the case with cholera. The bacteria that causes cholera (Vibrio cholera), a highly contagious diarrheal disease, can be quickly passed to large numbers of people through contaminated water in crowded and poorly-resourced settings such as urban slums or refugee camps that have poor access to clean water and sanitation. Rainfall further spreads the contaminated water, sustaining the outbreak. Population factors, such as undernutrition further worsen the disease. Undernourished people are at greater risk of severe cholera infections and of dying from the infection.

Figure 3: Factors contributing to cholera outbreaks.

The case of Ebola, a zoonotic infection

Most vaccine-preventable outbreaks are due to pathogens which circulate constantly among humans, causing spikes in disease when population and environmental conditions allow. Ebola, however, is a zoonotic infection, meaning that the normal reservoir for the pathogen is among animals, most likely bats. Ebola outbreaks among humans are triggered when people come into contact with infected animals (such as through the consumption of bush meat from infected primates), become ill and then pass the virus to other humans where it spreads until it can be contained.

Predicting when and where the virus will strike and spark an outbreak is thus very difficult, which significantly adds to the challenges of planning for, controlling and mitigating the impact of outbreaks. Ebola is one of several diseases of zoonotic origins that has the potential to ignite a global pandemic, according to USAID.

The Repercussions of Vaccine-Preventable Outbreaks

While outbreaks of measles and Ebola have been widely covered in the news media, a less visible topic has been the significant – and sometimes long-term – health and economic repercussions that come along with outbreaks of these and other diseases.

Repercussions on health systems

By definition, an outbreak is the occurrence of disease in a population that rises above expected levels. Although contingency plans may be in place for dealing with an outbreak, health staff, funding, medical supplies and other resources are often diverted to outbreak control, weakening the provision of other health services. In one example from Burkina Faso in 2007, meningitis epidemics disrupted health services at every level. Impact on all people seeking healthcare included longer wait times to be seen, increased time for lab test results, higher stress among caregivers and an increase in the number of misdiagnoses by overtaxed health care workers (HCWs).

Repercussions for healthcare workers

The burden on HCWs, in fact, extends beyond exhaustion and the mental toll of working in outbreak conditions. Health workers themselves are at significant risk of becoming victims of an infectious disease outbreak and passing on the infection to others, in particular before the infectious agent has been identified. HCWs can account for a substantial proportion of disease cases. A recent study using data from historical outbreaks of Ebola in Guinea and Nigeria, found that (had a fully effective vaccine been available at the time of those outbreaks) prophylactically vaccinating healthcare workers would have decreased the size of the Ebola epidemics in those countries by 60-80%. In the US, researchers estimated that ensuring full vaccination of healthcare workers would prevent more than 45% of exposures to pertussis that occur in healthcare settings. These are only two of many examples illustrating the disproportionate burden of disease cases among HCWs, all of which highlight critical gaps in vaccine coverage among people at significantly increased personal risk, and risk of infecting others. (For more on the WHO’s recommendations for immunizing health care workers.)

Repercussions of every kind: The Ebola firestorm

Outbreaks of exceptionally deadly infectious diseases such as Ebola can cause a cascade of events affecting every person and sector in a community and thus represent a firestorm of all the potential repercussions of an outbreak occurring at once. Huber et al described the devastating and far-reaching impact of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, including more than half a million people experiencing food insecurity, school closures lasting more than 7 months, tens of thousands of children orphaned, a huge proportion of the health workforce killed by the disease, infant, maternal and child deaths from lack of skilled health workforce and a 97% reduction in surgical capacity, to name a few. A second study projected that the crippling of immunization programs resulting from the Ebola outbreak could double the number of people at risk for measles, ultimately killing nearly as many people as Ebola itself.

Economic repercussions: costs of outbreaks

Adding to the secondary health and societal costs of infectious disease outbreaks are the actual monetary and economic impacts, which are significant even in a relatively small and quickly contained outbreak. The larger and longer an outbreak, the more significant its macroeconomic impacts on productivity, import & export losses, reduced tourism revenue and consumption.

From cholera to measles to Ebola, health economists have published several studies on the economic impact of outbreaks, covering direct costs of outbreak management to slowed national economic growth as a result of outbreaks. Direct costs to health systems include outbreak investigation costs such as personnel, supplies, travel expenses to find people exposed to infection and outbreak containment efforts including vaccination or prophylactic treatment costs for those exposed. Costs to individual families seeking treatment can be significant and have long-term economic consequences. Productivity losses and reduced consumption and revenue directly affect nations dealing with outbreaks, but shifts in imports and exports internationally can impact other nations economically, despite not being directly affected by the outbreak. Just some of the economic repercussions can be found in the cases below:

- A measles outbreak of 3 cases in Iowa, USA in 2004 cost the state Department of Public Health more than $140,000 in direct costs over a 2-month period to contain and manage the outbreak.

- Two meningococcal meningitis outbreaks in Brazil resulted in US$128k (9 cases, 2007) and US$34k (3 cases, 2011) direct costs to the health system

- A 2007 epidemic of bacterial meningitis in Burkina Faso cost the health system US$7.1 million, nearly 2% of the entire annual health budget for the small African nation

- A 2014 measles outbreak in Micronesia cost approximately US$4 million in direct costs, lost caretaker productivity and significant outbreak containment expenses. This amount is equal to the entire annual budget for education in the small island nation.

- A study of the economic burden of cholera in Africa found that 110,000 the cases of cholera reported in 2007 alone resulted in economic losses to the continent of $43.3 million, $60 million and $72.7 million US dollars, assuming life expectancies of 40, 53 and 73 years respectively.

- A study of a cholera outbreak in Peru in 1991-92 estimates that the national economy conservatively suffered more than US$50 million in economic losses due to reduced tourism revenue, reduced revenue on export of goods and lower domestic consumption as a result of the outbreak of cholera.

- Researchers estimated the impact of a hypothetical multi-country disease epidemic on US exports, and suggest that a widespread epidemic affecting 9 Asian countries could reduce US exports by US$8-41 billion and place more than a million export-related US jobs at risk.

- In a comprehensive accounting of the costs of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, Huber et al estimate the economic and social costs to have been US$53 billion, of which US$18.8 billion was attributed to non-Ebola deaths.

Outbreak Prevention and Preparedness

The prevention, mitigation and control of infectious disease outbreaks is becoming more urgent, while the number of emerging diseases increases, populations are more mobile and economies are stretched thin. Addressing infectious disease outbreaks must be a high political priority, requiring investments of both financial support and political will. But investments in what exactly?

It will come as no surprise that vaccination features prominently in our “TOP FIVE” list of investments that must be made to better prevent and prepare for outbreaks of infectious disease. What may be surprising is that financing, purchasing and delivering vaccines to the general population is only one of the necessary steps towards ensuring that the full potential of immunization can be realized in helping to prevent, mitigate and control outbreaks. Clear and actionable preparedness plans, robust health systems with increased access to health care, and significantly increased investments in disease surveillance and health communication round out our list.

Top Five Investments In Outbreak Prevention And Preparedness

1. Investment in health systems, including routine immunization

A country’s ability to prevent, detect and respond to outbreaks is tied to the strength and capacities of its health system overall. As such, a 2018 multi-stakeholder outbreak preparedness framework includes strengthening overall public health system capacity as the first of four pillars in the prevention of significant disease epidemics and pandemics.

National and subnational health systems supported by recommended levels of funding, high political priority and strategic planning processes that include the integration of emergency preparedness and everyday health systems operations are more resilient to emergencies such as disease outbreaks, and can recover more quickly. A 2016 WHO-led consultation with countries in the African region found that health systems and health security-related structures functioned independently from one another, but that strong support existed for the integration of emergency prevention and preparedness in broader health systems.

Given the high proportion of outbreaks due to vaccine-preventable infectious diseases, immunization has an especially important role to play in the prevention of disease outbreaks, and is thus critical for emergency prevention and preparedness.

2. Full immunization for health workers

High coverage of routine immunization is a critical firewall to prevent outbreaks from occurring, and vaccination of healthcare workers is especially critical to minimizing the spread of an emerging outbreak. Several studies have demonstrated the significant return on investment to be had by ensuring HCWs are fully immunized, given that HCWs often account for a disproportionately large number of disease cases. In the US study looking at prevention of the spread of pertussis referenced above, the financial return on vaccinating healthcare workers in hospitals was estimated to be nearly two and a half times the cost invested. A similar study of pertussis vaccine and HCWs in the Netherlands estimated the return on investment to be four times as great as the initial cost.

3. Actionable preparedness plan

Despite strong evidence that prevention and preparedness provide a sizeable return on investment, compared to the costs of an unchecked outbreak of disease, between 2016 and 2018 only one third of countries had assessed their own capacity to prevent, detect and control disease outbreaks.[1] That number has now risen to just under half, but nearly 80% of countries who have completed a preparedness assessment are wholly or partially unprepared for an outbreak of disease.[1] Experts argue that the cycle of panic and neglect in addressing disease outbreak readiness is a crisis of global proportions, and one which can only be broken by implementing and monitoring concrete preparedness plans.

4. Public health communications

Following recent global disease events like Ebola and SARS, which ignited global panic about the outbreaks and their impact, recognition has been increasing of the importance of consistent, clear and culturally sensitive communication with the public around health issues. Investment of money and time in this area, however, still lags behind the need. The WHO’s Outbreak Communication guidelines emphasize not only what needs to be done to communicate during an outbreak, but also the importance of building and maintaining trust in national and health authorities among all communities as a foundation for health communications and care seeking overall. Trust in an existing foundation of open, clear communication can help immunize against panic and increase compliance with measures intended to control and end outbreaks.

5. Infectious disease surveillance

The importance of disease surveillance, robust enough to detect outbreaks early, cannot be overstated, and yet, it is an area that is often poorly integrated in the broader public health system, and is chronically underfunded. Considered an essential public health capacity, investments in surveillance as it relates to outbreak detection and control are likely to have important benefits for other health priorities and diseases. For example, polio detection systems in the Americas were leveraged to better detect measles and rubella. Likewise, laboratory experience with measles and rubella surveillance led to the early detection and response to the H1N1 influenza virus in Mexico in 2009.

In summary, the specifics of the strategy for implementing each of these actions vary based on the type of outbreak. For example, the current vaccination strategy for Ebola includes finding and vaccinating all people who have come in contact with someone who has the disease (and all of those contacts’ contacts) to form a “ring” of immunity around disease cases. By contrast, measles and pertussis vaccines are recommended for all children worldwide during early childhood. Despite such differences in the specific approach needed, each of these five areas above are critical for mitigating the immediate impact and secondary repercussions of all future outbreaks.

[1] Jonas, Katz, et al. Call for independent monitoring of disease outbreak preparedness. BMJ. 2018;361:k2269 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2269

Editorial Commentary

“We are witnessing an apparent increase in the magnitude and frequency of outbreaks due to vaccine-preventable diseases, as adroitly described in this VoICE Featured Issue. Such outbreaks are, by definition, preventable and thus a tragedy, resulting in pointless deaths, countless disabilities, loss of productivity, and economic costs. We must do better. We call on policy makers, community leaders, and the global public health community to improve surveillance systems to detect outbreaks as early as possible, improve vaccination coverage to ensure all children are appropriately immunized, and effectively communicate the benefits of vaccination so trust in public health is restored. We will face new infectious disease threats. We must control those diseases for which we already have safe and effective vaccines so we are best prepared to deal with the emerging ones.”

William Moss, MD, MPH

Interim Executive Director, International Vaccine Access Center

William Moss, MD, MPH is Interim Executive Director, at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s, International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC), a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist who has dedicated the last three decades to improving the lives of children through better treatment and prevention of infectious disease. Dr. Moss has made significant contributions in many areas, including HIV, malaria, complex humanitarian emergencies and especially measles, for which he is a member of the World Health Organization’s expert Working Group on Measles and Rubella.