The story of immunization is often headlined with the remarkable health benefits—millions of lives saved, and illnesses and hospitalizations prevented. But the true impact of vaccination is even more far-reaching, touching many areas of people’s lives from supporting early childhood growth and development to improving educational outcomes and productivity, promoting economic stability, and helping to address equity gaps: It’s seemingly impossible to undersell the importance of vaccination.

This World Immunization Week, the VoICE editors highlight some of the broader benefits of immunization—not only helping to prevent illness and save lives, but also promoting healthy development, productivity, economic stability, and equity for all.

Key Messages

- Only looking at the direct impact of vaccination on morbidity and mortality grossly underestimates the wider value of vaccination on overall health and development

- Several studies show that immunization has the potential to increase productivity by averting preventable illness

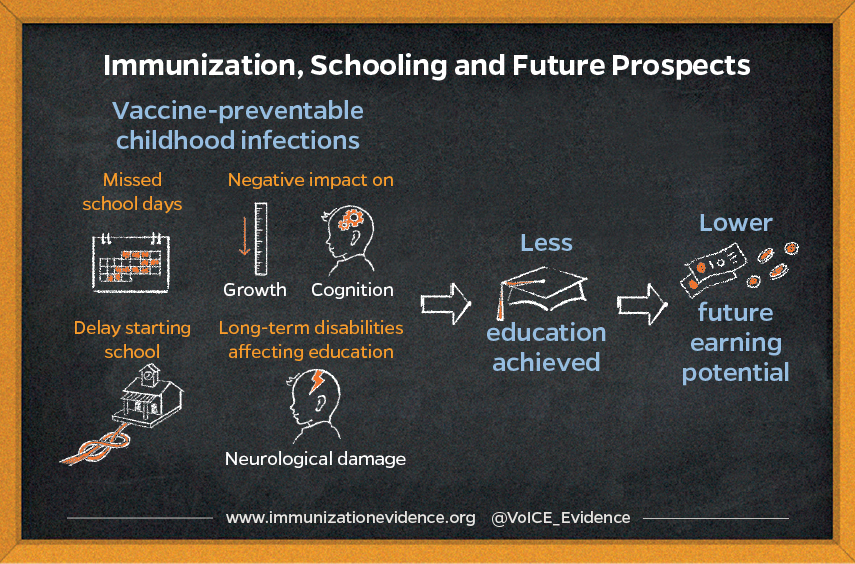

- Vaccines are associated with improved cognitive ability, education, and healthy physical development – which translates into increased economic productivity

- Vaccine-preventable diseases disproportionately affect the poorest children and families, but immunization can be a cost-effective tool to improve equity across geographies, gender, and marginalized populations

Preventing Pandemics Supports Economic Stability

The global health community is now facing an unprecedented challenge in the COVID-19 pandemic. As countries across the world attempt to slow the virus’s spread, this event has become a potent reminder of the vital importance of vaccination; we are seeing today just how much an infectious disease outbreak can ravage both national and global economies. Vaccines are important tools to help avert potentially catastrophic health costs that arise from preventable infectious disease outbreaks. Several studies have found that vaccines can bring additional stability to national economies by preventing the high costs incurred by illnesses.

- A 2009 study in Africa found an economic loss of US $43-72 million resulting from the 110,837 cases of cholera reported in 20071.

- Researchers modeling the costs of potential pandemic influenza in the UK estimated costs of illness between £8.4 and £72.3 billion depending on the severity of the fatality rate, and even larger still for an extreme pandemic. In such a scenario, vaccination could limit the overall economic impact of pandemics2.

Vaccines Help Promote Productivity

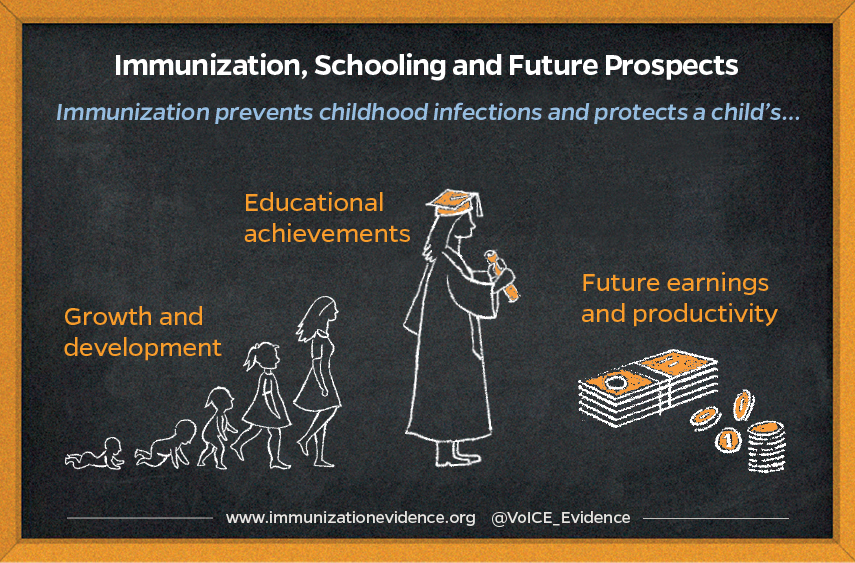

Productivity—the measure of output by a working individual or a population—is an important determinant of standard of living. By preventing illness, vaccination can help promote productivity by supporting healthy cognitive development and success in school, ultimately helping children achieve their full potential across the lifespan.

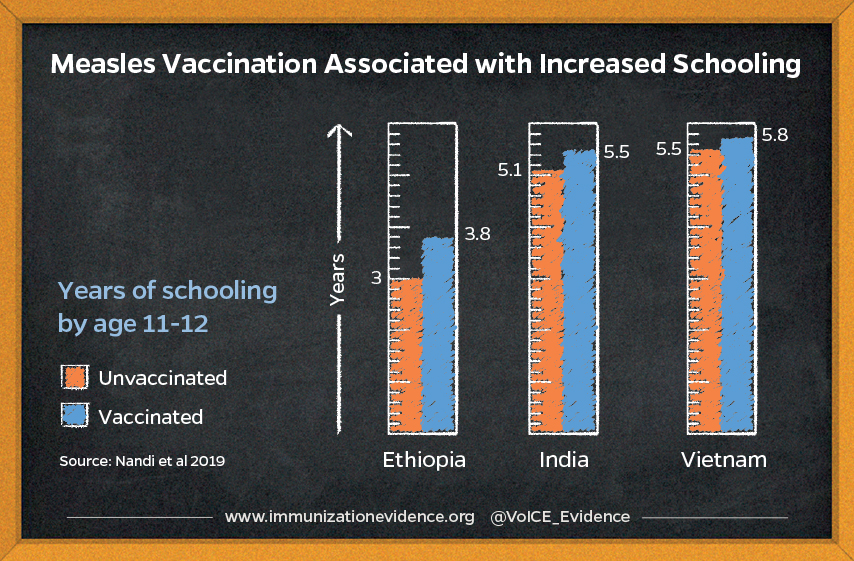

- A 2019 longitudinal study followed almost 6,000 children in India, Ethiopia, and Vietnam throughout childhood, finding that those vaccinated against measles scored better on cognitive tests of language development, math, and reading compared to children who did not receive measles vaccines3.

- In a 2011 study in the Philippines, children vaccinated against six diseases performed significantly better on verbal reasoning, math and language tests than unvaccinated children4.

- Vaccine-preventable diseases lead to both work and school absenteeism, which can negatively impact productivity and cause a substantial economic burden. A Norwegian study found that children hospitalized with rotavirus were absent from daycare for 6.3 days, on average, and 73% of their parents missed work5.

Vaccines Support Healthy Child Growth and Development

Some vaccine-preventable diseases can delay or interrupt normal growth and development in early childhood, leading to long-lasting damage that can adversely impact children for the rest of their lives. Persistent or recurrent infections in early life can lead to poor growth and stunting, which in turn can adversely affect adult health, cognitive capacity, and economic productivity.

- Childhood vaccination programs can be a tool for mitigating undernutrition in developing countries. Children enrolled in Universal Immunization Programs observe improvements in terms of age-appropriate height and weight as per results of a study focused on 4-year-old children in India. On average, height and weight deficits were reduced by 22-25% and 15% respectively6.

- A study in Kenya revealed that polio, BCG, DPT and measles immunization had protective effects with respect to stunting in children. In children under the age of 2 years, children immunized with polio, BCG, DPT, and measles vaccines were 27% less likely to experience stunting compared to unimmunized children7.

- A 2013 study conducted in several developing countries found that children with moderate-to-severe diarrhea grew significantly less in length in the two months following an episode of illness compared to age- and gender-matched controls8.

- Modeling of data from India’s 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey indicated that vaccinations against DPT, polio, and measles were significant positive predictors of a child’s height, weight, and hemoglobin concentration. Such indicators, in turn, influence children’s cognitive development and hence the future supply of skilled labor that is critical for economic growth9.

Tackling Immunization Inequities Can Have Substantial Benefits

While huge progress has been made in introducing and scaling up access to important vaccines, we still have a long way to go. There is significant evidence of inequities in vaccine coverage that exists between and within countries, as well as between and within different populations. In Gavi-supported countries, there are still an estimated 10.4 million “zero-dose children” who have not received any doses of DTP-containing vaccine.

- Results of a 2019 study in Kenya found that immunization outreach for remote or hard-to-reach populations can still be highly cost-effective. The study found that failure to vaccinate hard-to-reach children against measles would result in more than 1,400 measles cases, 257 deaths, and cost nearly U.S. $10 million over the course of 4 years, mainly due to productivity losses from caretakers missing work10.

- A 2018 study found that children of poor labor migrants living in Delhi, India are much less likely to be fully vaccinated than the general population and thus are at greater risk of vaccine-preventable diseases. Only 31% – 53% of children from migrant families were fully immunized (against 7 diseases) by 12 months of age, compared to 72% in the overall population of Delhi — with recent migrants having the lowest rates11.

- Researchers looking at vaccination coverage in 45 low- and middle-income countries found that maternal education is a strong predictor of vaccine coverage. Children of the least educated mothers are 55% less likely to have received measles-containing vaccine and three doses of DTP vaccine than children of the most educated mothers12.

The evidence shows that vaccines offer cross-cutting benefits for individuals, families, communities, and truly everyone across the globe. Cross-disciplinary research from many global health perspectives demonstrates that vaccines as a versatile, impactful tool that does so much more than just preventing millions of deaths and illness every year: Vaccines benefit global economies, boost productivity, and help close gaps in equity.

As we respond to COVID-19, the reality that infectious disease outbreaks anywhere in the world can quickly become a threat anywhere further highlights the importance of investment in vaccination as a part of strong, resilient health systems. As countries across the world grapple with containing the COVID-19 outbreak, we must also work together to ensure that the world’s most vulnerable children don’t miss out on the vaccines that prevent devastating illnesses like measles, polio, diarrhea, and pneumonia. In the face of this current challenge, it’s essential that we work together to protect essential health services like immunization to ensure that all people have a shot at living a healthy life protected from preventable disease.

Visit the VoICE World Immunization Week 2020 Social Media Toolkit for messaging and images to promote the broad benefits of vaccines. The toolkit is also available on the official World Immunization Week 2020 website.

References

- Kirigia, J.M., Gambo, L.G., Yolouide, A., et al 2009. Economic burden of cholera in the WHO African Region. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 9(8). doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-8

- Smith, R.D., Keogh-Brown, M.R., Barnett, T., et al 2009. The economy-wide impact of pandemic influenza on the UK: a computable general equilibrium modeling experiment. BMJ. 339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4571

- Nandi A, Shet A, Behrman JR, et al. 2019. Anthropometric, cognitive, and schooling benefits of measles vaccination: Longitudinal cohort analysis in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. Vaccine. 37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.06.025

- Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Shenoy, E. S. (2011). The effect of vaccination on children’s physical and cognitive development in the Philippines. Applied Economics, 44(21), 2777-2783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.566203

- Edwards CH, Bekkewold T, Flem E. 2017. Lost workdays and healthcare use before and after hospital visits due to rotavirus and other gastroenteritis among young children in Norway. Vaccine. 35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.037

- Anekwe, T.D., Kumar, S. 2012. The effect of a vaccination program on child anthropometry: Evidence from India’s Universal Immunization Program. Journal of Public Health. 34(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds032

- Gewa, C.A. and Yandell, N. 2011. Undernutrition among Kenyan children: contribution of child, maternal and household factors. Public Health Nutrition. 15(6). https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001100245X

- Kotloff, K.L., Nataro, J.P., Blackwelder, W.C., et al 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 382(9888). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2

- Bhargava, A., Guntupalli, A.M., Lokshin, M. 2011. Health Care Utilization, socioeconomic factors and child health in India. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 43(6). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932011000241

- Lee BY, Brown ST, Haidari LA et al. 2019. Economic value of vaccinating geographically hard-to-reach populations with measles vaccine: a modeling application in Kenya. Vaccine. 37(17). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.007

- Kusuma YS, Kaushal S, Sundari AB, et al. 2018. Access to childhood immunization services and its determinants among recent and settled migrants in Delhi, India. Public Health. 158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.006

- Arsenault, C., Harper, S., Nandi, A., et al. 2017. Monitoring equity in vaccination coverage: A systematic analysis of demographic and health surveys from 45 Gavi-supported countries. Vaccine. 5(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.041