Conflict and forced migration – resulting in disruption of communities and health systems – amplify the risk factors for infectious disease and increase the urgency of preventive measures such as immunization. While disease outbreaks of measles, cholera, meningitis and even polio in refugee camps may be the most widely covered issues related to immunization in conflict-affected areas and populations, this VoICE Featured Issue explores some of the less-visible, but equally critical aspects. Immunizations play an important role in these settings, considering the threat of malnutrition and antimicrobial resistance, economic pressures, and the urgent need for responsive policies.

A selection of VoICE evidence in this issue

Key Points:

- Malnutrition and infectious disease – together set off a dangerous and potentially life-threatening cycle – represent the greatest twin threat to health during humanitarian emergencies. Vaccines can help interrupt the cycle and mitigate some of the risk to refugees and conflict-affected populations.

- The spread of antimicrobial resistant organisms and infections may be increased in the conditions present in areas experiencing conflict and significant population displacement.

- The provision of immunizations to refugees can be cost-effective and may avert significant treatment-related expenses from infections down the road.

- Preparing for emergencies, especially at the policy level, is a critical success factor for countries affected by humanitarian crises and those hosting displaced populations.

Exhausted, hungry, not sure where they will sleep or bathe, or for how long they may have to stay in a makeshift camp…displaced people arriving in refugee camps are often stepping into a perfect storm of risk factors for poor health and vaccine-preventable infections. Exhaustion, malnutrition and poor access to clean water and sanitation all contribute to increasing a person’s risk of infectious disease. Having taken only what they could carry, these people are also living in poverty (some are newly poor, having abandoned possessions and property to flee the fighting), which is a well-known risk factor for developing vaccine-preventable diseases and further impoverishment. A scene like this only hints at the long list of health risks and challenges facing refugees fleeing from, and families living in, conflict-ridden zones.

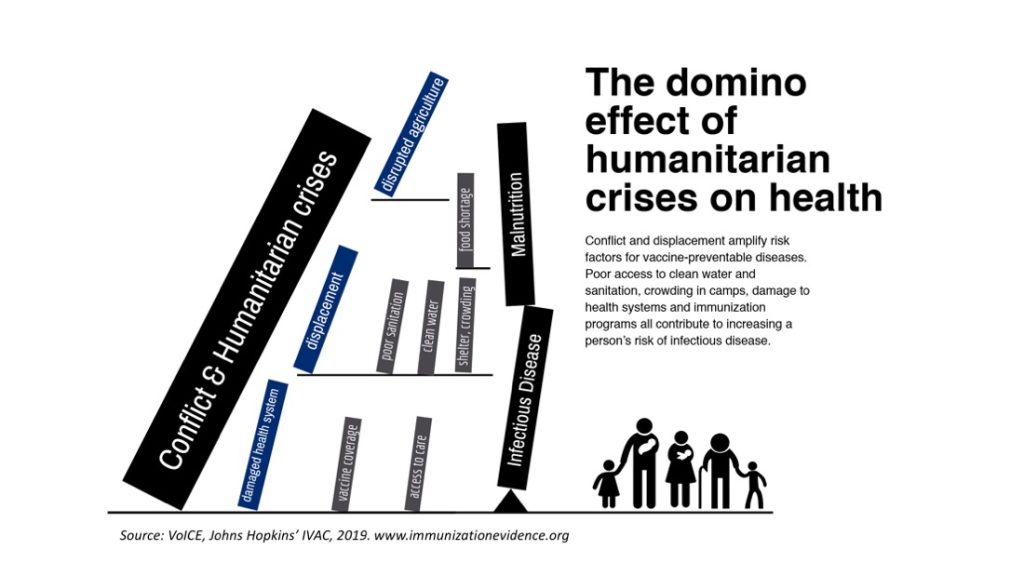

Figure 1: The domino effect of humanitarian emergencies and infectious disease

Conflict and forced migration – resulting in disruption of communities and health systems – amplify the risk factors for infectious disease and increase the urgency of preventive measures such as immunization. While disease outbreaks of measles, cholera, meningitis and even polio in refugee camps may be the most widely covered issue related to immunization in conflict-affected areas and populations, in this VoICE Featured Issue we will explore some of the less visible, but equally critical aspects of immunization in these settings including malnutrition, antimicrobial resistance, economics and policy.

Malnutrition and infectious disease

Figure 1 illustrates the domino effect of conflict and other complex humanitarian emergencies on health, in particular nutrition and risk of infectious disease. Ultimately, malnutrition and infectious diseases are significantly worsened in such situations and are responsible for a majority of deaths, even far outstripping trauma and violent injuries due to fighting in areas of active combat, according to a 2011 Technical Report from the World Bank. In a recent Technical Report in the journal Pediatrics, researchers noted that children under 5 years of age bear the greatest burden of indirect conflict-associated mortality, largely due to disruptions in health services, such as vaccination, and access to food.

Several studies have concluded that respiratory and gastrointestinal infections are the two leading causes of death during complex humanitarian emergencies (CHEs) “…independent of geography, time and crisis-type…”, according to a recent review. The authors of this review go on to say, given the close cyclical relationship between infectious diseases and malnutrition, immunization could help defend people against the infectious disease risks that come with malnutrition, a problem which is exceedingly common in humanitarian crises. Pneumococcal, Hib, measles, rotavirus and cholera vaccines can help protect populations who are especially vulnerable to malnutrition .

For more on the nutrition and disease cycle, see our VoICE Featured Issue on the links between malnutrition and infectious disease.

Antimicrobial resistance in refugee settings

Antimicrobial resistance – or the ability of some bacteria to survive treatment with antibiotics – is another heavy burden that rests on those living in and fleeing from conflict zones. A 2018 systematic review found that a quarter of migrants who fled to the European region either carried or were infected with antimicrobial resistant organisms, and that this rate rose to a third of all refugees or asylum seekers.[1] Contributing factors include crowded living conditions with variable access to sanitation, poor overall health, lack of access to vaccines, as well as the exposure to new pathogens stemming from the mingling of large numbers of people originating from geographically distinct areas.

Availability of treatment and other health services in areas of conflict or in newly established refugee camps may be very low, and treatment for antibiotic resistant infections can be particularly difficult and costly, even in well-resourced health systems.

A large review of the use of vaccines in complex humanitarian emergencies stated that the reduction of antimicrobial resistance was an important indirect effect of the use of vaccines in such settings. Immunization helps curb the spread of antimicrobial resistant organisms by preventing infections that might otherwise be treated with antibiotics, thereby decreasing opportunities for the development of resistance. Not only do vaccines decrease the use of antibiotics, but they prevent occurrence of resistant infections. Use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in South Africa has led to significant declines in invasive pneumococcal disease cases caused by bacteria that are resistant to one or more antibiotics. In fact, the rate of infections resistant to two different antibiotics declined nearly twice as much as infections that could be treated with antibiotics.

The economics of immunization and conflict

The conditions present in refugee settings are both logistically challenging – with potentially large numbers of people moving in and out, lack of health records, sanitation, supplies, etc. – and ripe for infectious diseases and outbreaks. These factors make it very difficult to provide enough emergency health and treatment services during emergencies, and such services take time and significant expense to establish. Although delivering vaccines in these settings is not without difficulty, the ability of immunization to prevent illness and disease spread, and to protect malnourished populations carries economic benefits.

Evidence from recent humanitarian crises in Somalia and South Sudan has shown vaccination against Hib and pneumococcal pneumonia would be cost-effective and could reduce pneumonia cases and deaths by nearly 20%. Similarly, researchers conclude that the use of the rotavirus vaccine to reduce diarrheal disease and deaths in Somalia, during its ongoing civil conflict would be cost-effective, even in the face of vaccine delivery challenges.

Where do we go from here?

The number of armed conflicts and forced displacements worldwide is at an all-time high. The majority of people displaced by conflict and other humanitarian emergencies are either internally displaced (within the borders of their country of origin) or flee to neighboring countries. This has led to the greatest burden of care for refugees being placed on developing countries who may themselves be struggling – both economically and programmatically, in terms of the delivery of health services such as immunization.

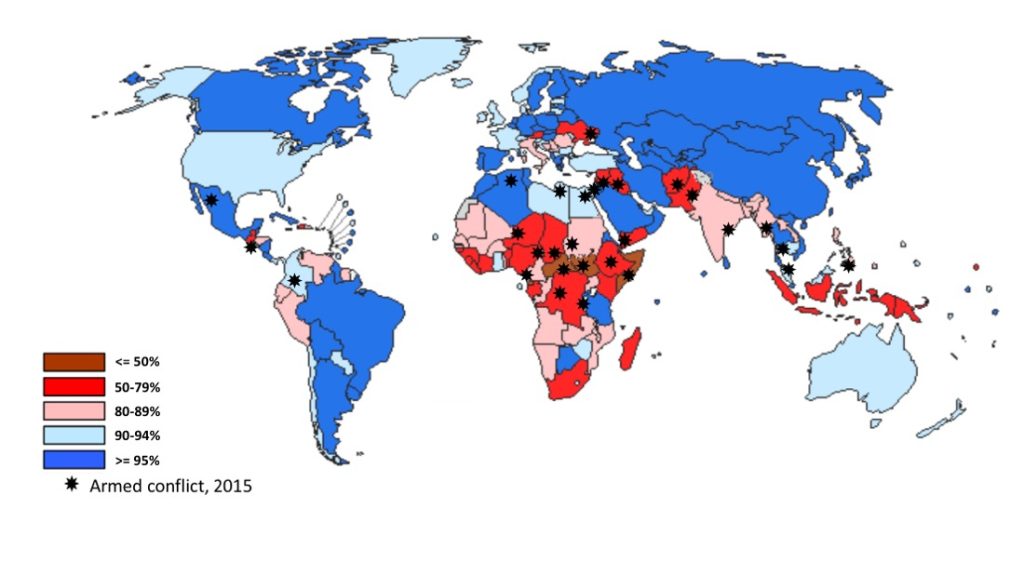

In the map in Figure 2 below you can see countries with active armed conflict in 2015, marked with a black star, overlaid on a map of the coverage of one dose of measles-containing vaccine – for which the WHO says 90% coverage is needed to avert disease outbreaks – during the preceding year (2014). Although it is not surprising that countries afflicted by conflict are also struggling to achieve high vaccine coverage, it is a reminder that political and health system fragility go hand-in-hand and that these fragile countries are also those most often called upon to help neighbors in crisis.

Figure 2: Armed conflict and low vaccine coverage often occur in the same places.

Measles coverage map: World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF coverage estimates. Available at http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/en

Armed conflict overlay: Adapted from: Kadir A, Shenoda S, Goldhagen J, et al. The Effects of Armed Conflict on Children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6)

There have been some notable success stories, for example in Yemen and the Syrian Arab Republic, where vaccination coverage has largely been sustained and is credited with averting a potentially significant burden of preventable infection. Credit for this success is due to the establishment of emergency preparedness procedures and policies in advance of crises and through coordinated programmatic and financial support from governments and partners such as the World Health Organization, UNICEF and non-governmental organizations. Thanks to the readiness of such partners, in October 2018, WHO and UNICEF succeeded in vaccinating more than 300,000 people in Yemen against cholera during a 4-day ceasefire.

The establishment of national policies addressing the health of refugees and migrants is essential step, and challenges abound in both developing and developed nations. In Bangladesh, an engaged health sector, quick government response and an existing multi-sector action plan for disease outbreaks in Bangladesh have been responsible for a robust and ongoing response to vaccine-preventable infections and very low vaccination coverage among Rohingya refugees arriving from Myanmar. In the European region, where more than 30% of the global migrant population resides, only one-third of countries had established policies for the immunization of migrants and refugees. In countries without such policies, many migrants and refugees miss out on vaccinations – either because it is unclear to providers who can be vaccinated and who pays, or because families are not made aware of the mechanisms or opportunities around vaccination.

Humanitarian crises and population displacement are not going away. Limiting the damage to the health of people in crisis will require the swift and broad use of health interventions such as vaccination, policies that help plan for the worst and engaged partners. Best stated by Peter Salama, head of the WHO’s Emergency Response division, “What we really need is international solidarity.”

[1] It is important to note that the greatest risk of AMR related to population displacement is to the displaced themselves. A report released by the World Health Organization last month on the health of refugees and migrants in the European region[1] notes that transmission of antimicrobial resistant infections almost exclusively affects those residing in refugee transit centers and settlements and does not pose an immediate threat to host populations.

For Additional Information:

To learn more about the relationship between immunization and conflict, migration and complex humanitarian emergencies, see related messages and evidence in the VoICE tool found here: https://immunizationevidence.org/search-immunization-evidence/?fwp_topic=conflict-and-humanitarian-emergencies

World Health Organization, Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European Region. No PUBLIC HEALTH without REFUGEE and MIGRANT HEALTH; 2018; Geneva, Switzerland. Found here: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-the-who-european-region-no-public-health-without-refugee-and-migrant-health-2018

World Bank. World Development Report 2011 Background Paper, Demographic and Health Consequences of Civil Conflict. 2011. Found here: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/9083/WDR2011_0011.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y