The battle to eliminate polio is one example of how immunization integration can be leveraged to strengthen health systems and build vaccine acceptance. Integration is one of the three pillars of the Endgame Strategy and is highlighted as a strategic priority in the Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) and in Gavi’s 5.0 strategy.

Immunization programs are among the most successful and important public health programs across the globe, reaching an estimated 85% of the world’s children1. Although immunization programs like the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) successfully reach the majority of the world’s children, other important health interventions may lack delivery mechanisms with the same scale as immunization. According to the CDC, “immunization reaches more children than any other single intervention.”2 The success of immunization programs means that they can also become an important platform for delivering additional health resources and services.

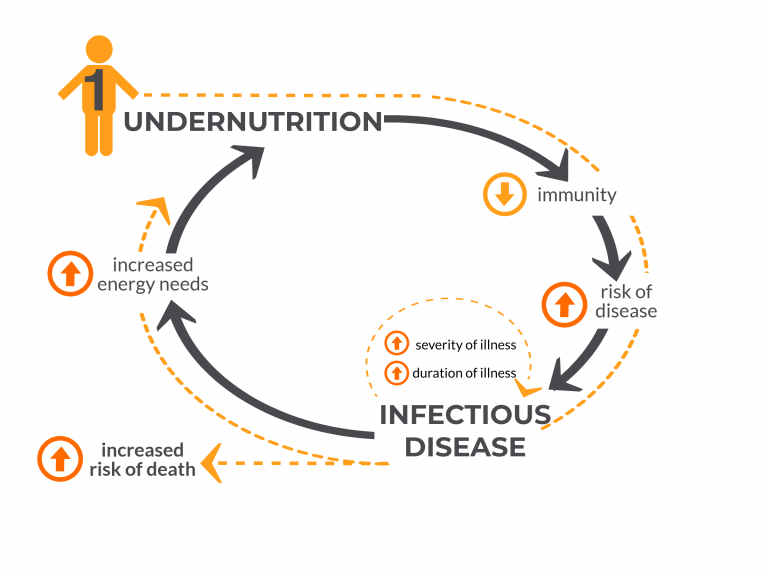

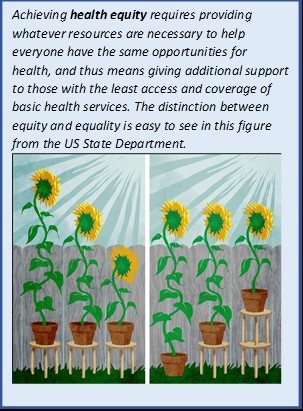

In many circumstances, populations may have particularly limited access or contact with services to address health issues such as malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies, malaria, access to family planning, and early infant diagnostics for HIV. Effective immunization integration can help strengthen health systems, providing more efficient and accessible health care for women and children.

The battle to eliminate polio is one of the examples for how immunization integration can be leveraged to strengthen health systems, particularly in the most vulnerable areas. Integration is one of the three pillars of the Endgame Strategy and is highlighted as a strategic priority in the Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) and in Gavi’s 5.0 strategy to ensure no one is left behind with immunization.

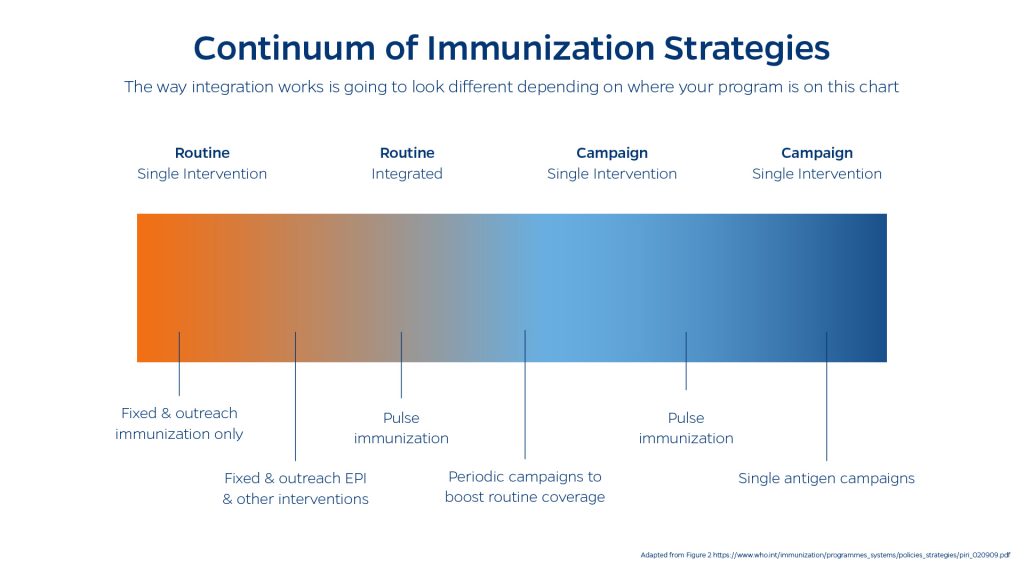

The Integration Continuum

There are many possible permutations of integrated health services. The WHO recommends that integration be viewed as a continuum of potential options, rather than as zero-sum options of “integrated” and “not integrated.” There are many different factors3 that need to be taken into account to determine the optimal strategy for integration of immunization services such as:

- selecting interventions that can be feasibly integrated;

- coordination across program levels;

- ensuring adequate training and workload for health workers;

- ensuring the participation of community based organizations, leaders, and volunteers

Integration and Community Acceptance of Vaccines

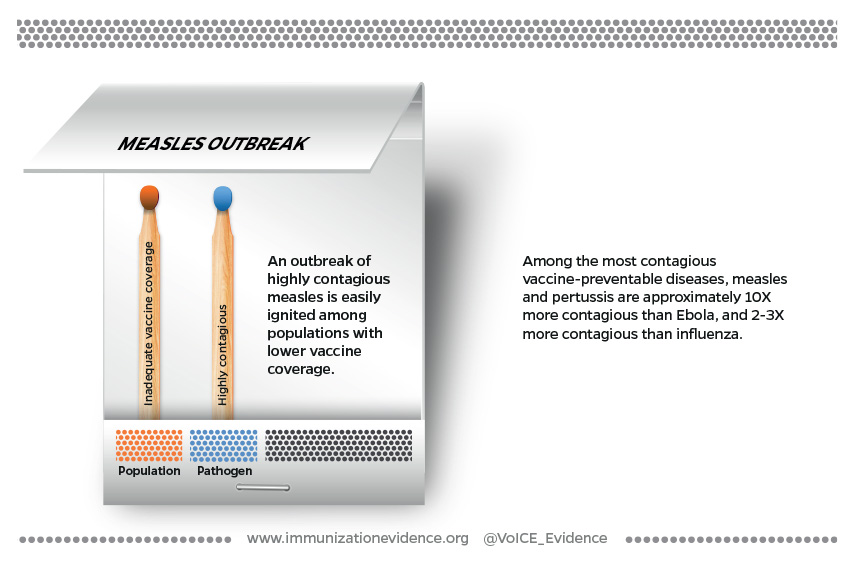

With vaccine hesitancy becoming a rising global threat, community engagement should serve as a cornerstone to the implementation and planning of health services. The co-delivery of immunizations with services that are prioritized by the target community can improve acceptability. Co-delivery of vaccines with priority services can also improve job satisfaction for frontline health workers by allowing workers to provide the range of services desired by community members. When community health workers in parts of India and Nigeria focused only on providing repeated polio campaigns, they were questioned by the community about why they only addressing a single disease that wasn’t a priority for many individuals in the area4.

“When talking about healthcare services in urban slums, an interviewee described that, ‘it’s not a matter of hard- to- reach but rather, hardly reached.’ Communities felt ignored by their government, and were thus mistrusting and sceptical of government or NGO intervention during polio vaccination rounds.”

Bellatin A, Hyder A, Rao S, et al. (2021)

In an investigation of 30 years of polio campaigns in Ethiopia, India, and Nigeria, researchers found that in all study countries, community hesitancy towards vaccines could be mitigated when health systems demonstrated responsiveness to the community’s priorities and needs4.

- Among pastoralist communities in East Africa, co-delivery of polio vaccines along with high-priority services like veterinary care, improved community acceptance of the vaccines5.

- In Ethiopia and Nigeria, OPV was increasingly delivered alongside Vitamin A, insecticide- treated nets, and deworming tablets, and CORE group volunteers engaged broadly in child health education6,7.

- India’s 107 Block Plan, developed in 2009, focused on routine immunization, sanitation8 practices, breastfeeding rates, and reducing diarrheal disease. One of major challenges in the final years of polio elimination in India was resistance from vaccine hesitant groups. One factor for successful elimination of polio in Uttar Pradesh was improving vaccine acceptance by packaging other basic healthcare services such as routine check- ups and essential medications9.

Evidence from the VoICE Compendium

The integration of maternal and child health interventions into immunization campaigns can lead to improved rates of immunizations and related healthcare interventions.

In an effort to reach children with vitamin A deficiency in the African countries of Angola, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, and Togo, vitamin A supplementation was administered during Polio vaccine campaigns. This led to a minimum coverage of 80% for vitamin A and 84% for polio vaccine in all of the immunization campaigns. During the second year of vitamin A integration into the polio vaccination campaign, coverage exceeded 90% for both vitamin A and polio vaccination in all four countries.

Immunization services can be integrated with family planning services to strengthen healthcare access for children and parents.

The total number of women accessing family planning services during the study period increased by 14% while DPT immunization rates for children remained consistent. In interviews, parents and providers found the integration of family planning and immunization services to be feasible and beneficial, indicating a win-win for both services.

Recent assessments of missed opportunities for vaccination (MOV) demonstrate that immunization coverage rates may also benefit from increased integration.

Children attending health facilities for vaccination, clinical care or other reasons, were not consistently being offered all of the recommended vaccines (57% for all clinic attendees, 25% for children attending for vaccination and 89% among those attending for medical consultation). Integrating immunization into primary care visits, health registers, and workflows can help reduce missed opportunities for vaccination.

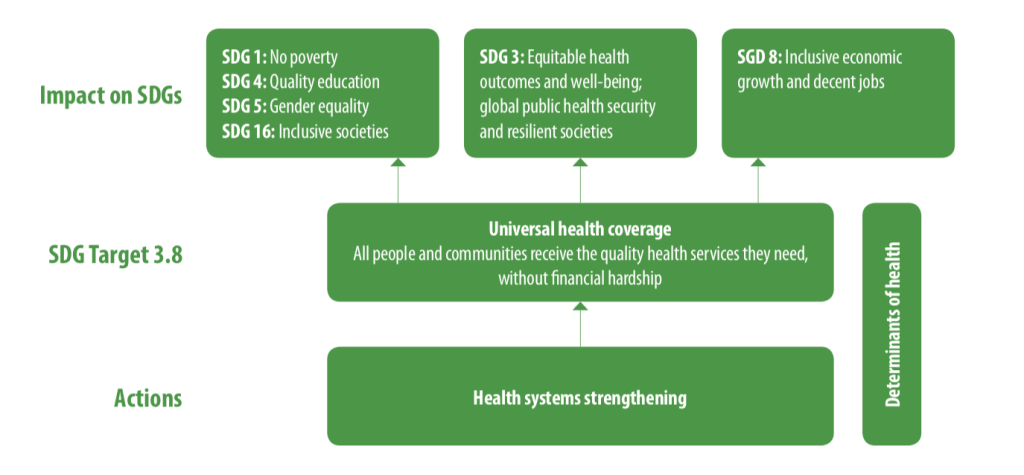

Immunization programs provide opportunities for cost-sharing and external funding when used alongside other health interventions.

BCG and DPT have the highest coverage of any vaccines worldwide and are typically administered within 6 weeks of birth. This timing offers the opportunity to deliver a range of early childhood development interventions such as newborn hearing screening, sickle cell screening, treatment and surveillance, maternal education around key newborn care issues such as jaundice, and tracking early signs of poor growth and nutrition.

Integration in the COVID-19 Era: Opening New Doors

“…as billions of dollars are being spent to support vaccine rollout, as much as possible, these funds should be used in ways that not only distribute vaccines as quickly and equitably as possible but also strengthen – rather than detract from – underlying PHC systems.”

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic may present an opportunity for new ways of working across health campaigns, including promising applications of integration. The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PCPPI) has published a brief summarizing how the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccination efforts can be leveraged to support long-term primary health care strengthening.

- Building systems for population health management

- Strengthening surveillance and information systems

- Formalizing mechanisms for multi-sectoral action and social accountability

- Strengthening quality management infrastructure and building sustainable supply chains

- Sustaining investments in the health workforce

A recent report published by WHO comprehensively documents the significant role played by polio eradication personnel during the pandemic, and urges strong action to sustain this network to deliver essential public health services after polio is eradicated.

Integrating with Intention

Simply integrating immunizations with other services is not sufficient to add value: It’s also key that integration must be implemented thoughtfully with appropriate attention paid to the context at hand. Well-integrated immunization programs can:

- Improve efficiency and reduce redundancy for frontline workers – saving them valuable time.

- Improve equity and coverage

- Improve community vaccine acceptance

Implementation Glossary

Integrated Service Delivery – the organization and management of health services so that people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways that are user-friendly, achieve the desired results and provide value for money.

Integration – The sharing of all or specific campaign components or functions by a specific program addressing a disease or health need with the broader health system and ongoing delivery of interventions through general health services.

Full Integration – Involves sharing of both operational and administrative functions and responsibilities and delivery of campaign interventions via primary health care (PHC). It occurs when interventions that were formerly delivered via independent health campaigns are delivered at the PHC level with other ongoing health services.

Partial Integration – Partial integration refers to a spectrum or continuum, in which campaigns share different operational and/or administrative components with any of the PHC system elements per the modified PHCPI framework—at the systems or inputs levels or both, while continuing to deliver services independently.

Health Campaign – A coordinated set of activities that targets resources to achieve a specific health goal or goals and is typically time-limited.

Collaboration of Campaigns – Partial integration of specific campaign components between vertical health programs (targeting different health problems) to improve efficiency and effectiveness of the vertical programs, but without co-delivery of interventions at the same service delivery points.

Periodic Intensification of Routine Immunization (PIRI) – A format with a range of options falling between the poles of routine services and campaigns. PIRI activities are intended to augment routine immunization services rather than be the primary means of providing it.

References

- PMNCH Knowledge Summary #25 Integrating immunization and other services for women and children. WHO. 2013. https://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/summaries/ks25/en/

- CDC. CDC Global Health – Immunization – Reaching Every Child. Published May 21, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/immunization/sis/every_child.htm

- World Health Organization. Working Together: An Integration Resource Guide for Immunization Services throughout the Life Course. World Health Organization; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276546

- Neel AH, Closser S, Villanueva C, et al. 30 years of polio campaigns in Ethiopia, India and Nigeria: the impacts of campaign design on vaccine hesitancy and health worker motivation. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(8):e006002. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006002

- Haydarov R, Anand S, Frouws B, Toure B, Okiror S, Bhui BR. Evidence-Based Engagement of the Somali Pastoralists of the Horn of Africa in Polio Immunization: Overview of Tracking, Cross-Border, Operations, and Communication Strategies. Global Health Communication. 2016;2(1):11-18. doi:10.1080/23762004.2016.1205890

- Asegedew B, Tessema F, Perry HB, Bisrat F. The CORE Group Polio Project’s Community Volunteers and Polio Eradication in Ethiopia: Self-Reports of Their Activities, Knowledge, and Contributions. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2019;101(4_Suppl):45-51. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-1000

- Bawa S, McNab C, Nkwogu L, et al. Using the polio programme to deliver primary health care in Nigeria: implementation research. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(1):24-32. doi:10.2471/BLT.18.211565

- Sukla P, Sharma KD, Rana M, Zaidi SHN. Polio eradication in India: New intiatives in sanitation. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25(1):74-76.

- Bellatin A, Hyder A, Rao S, Zhang PC, McGahan AM. Overcoming vaccine deployment challenges among the hardest to reach: lessons from polio elimination in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):e005125. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005125