In August of 2020, the World Health Assembly adopted the global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. Vaccines against the human papillomavirus (HPV) can prevent the vast majority of the world’s 570,000 annual cases of cervical cancer. Increasing access to the HPV vaccine, as well as screening and treatment, for women and girls living in low- and middle-income countries is an important step for global gender equity, potentially leading to the elimination of cervical cancer within the next 100 years.

HPV Vaccination is a Critical Step Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination

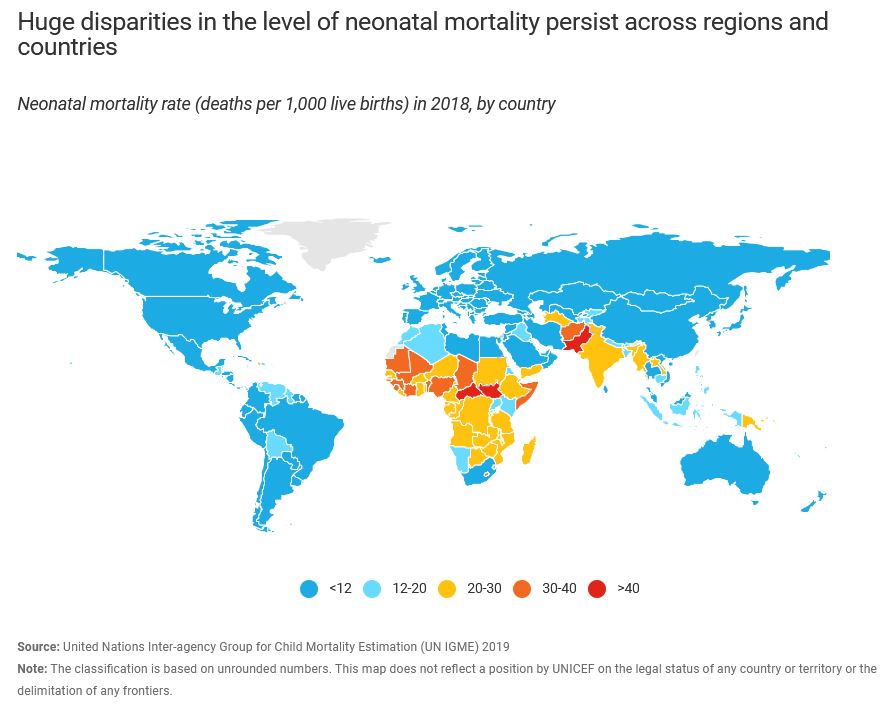

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a vaccine-preventable infection that causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer. According to the Global Cancer Observatory1, infection with HPV led to an estimated 570,000 cases of cervical cancer and 311,000 cervical cancer deaths worldwide just in 2018.

The overwhelming majority of women impacted by this preventable cancer live in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). According to a 2020 study2 from The Lancet Global Health, “Approximately 84% of all cervical cancers and 88% of all deaths caused by cervical cancer occurred in lower-resource countries.” Across many regions of Africa, cervical cancer caused by HPV is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women.

In August 2020, a global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem was adopted by the Member States of the World Health Organization (WHO).

WHO recommends the following targets or milestones that each country should meet by 2030 to be on track to eliminate cervical cancer within the century:

- 90% of girls fully vaccinated with the HPV vaccine by the age of 15;

- 70% of women screened using a high-performance test by the age of 35, and again by the age of 45; and

- 90% of women identified with cervical disease receive treatment.

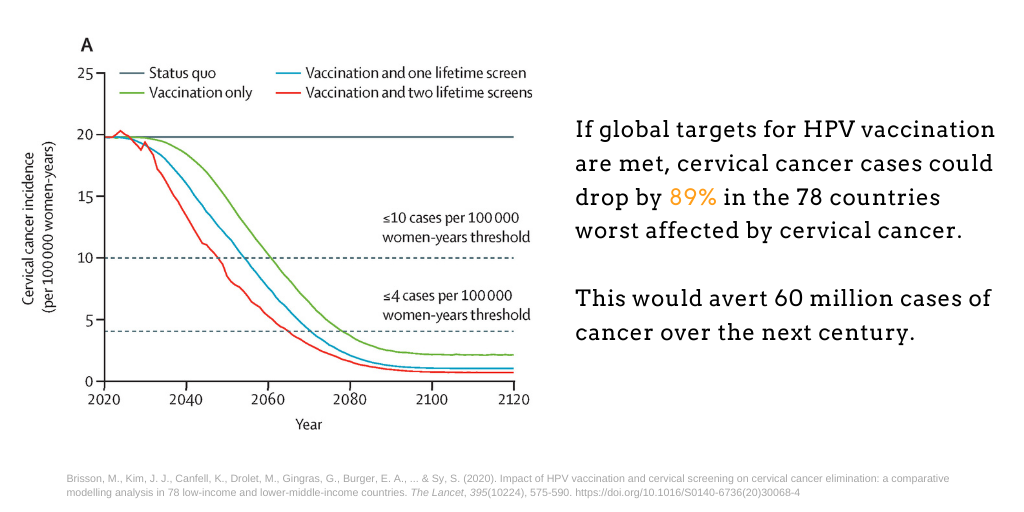

The results of a 2020 analysis3 from Brisson et al. found that just by meeting HPV vaccination targets, cervical cancer cases could drop by 89% within a century in the 78 countries worst affected by the disease. Meeting targets for cervical cancer screening and treatment would further reduce cervical cancer cases by 97%, averting 72 million cervical cancer cases over the next century.

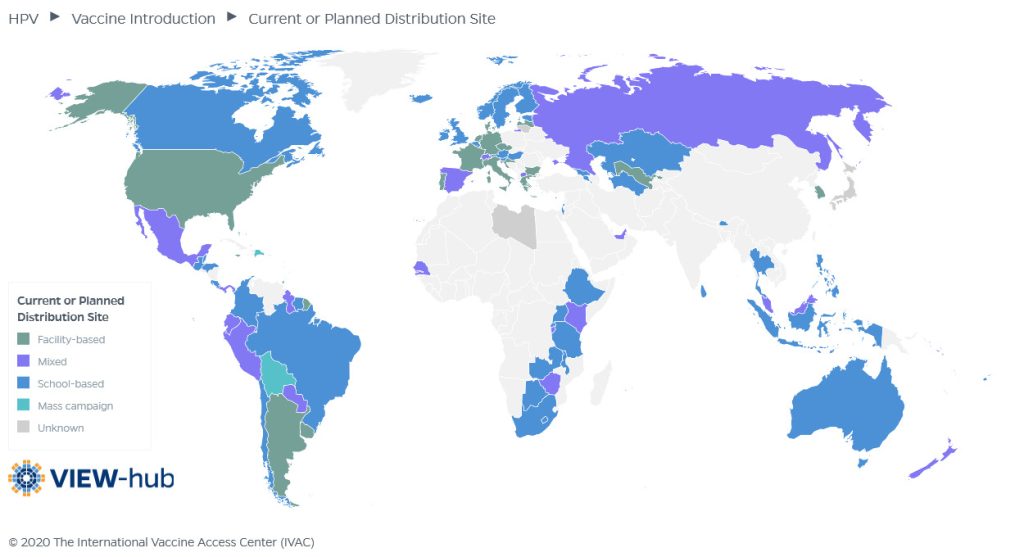

VIEW-hub: Mapping HPV Vaccine Progress

VIEW-hub is an interactive mapping platform for visualizing up-to-date data on vaccine use and impact. In 2020, VIEW-hub launched a new module on HPV vaccination providing users with updated maps and data tables to track country-level progress for rollout of vaccines.

Through VIEW-hub, users can access and download immunization advocacy resources including global data downloads, maps and country profiles. For HPV vaccination, VIEW-hub provides data on current program types, current/planned vaccine product, current dosing schedule, current or planned distribution sites and target populations by sex.

Broad Benefits of HPV Vaccine

While HPV is most commonly associated with cervical cancer, this viral infection also can cause a number of other cancers in both men and women. These other cancers include anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile, and head and neck cancers.

Currently, three vaccines are available which offer varying levels of protection against HPV-associated cancers. The vaccines all contain protein particles without live virus but they differ in the number of viral subtypes that are included. Bivalent (2 subtypes) and quadrivalent (4 subtypes) vaccines are prequalified by the WHO and the third option is a nonavalent (9 subtypes) vaccine that is primarily available in high-income countries. All three vaccines include HPV genotypes 16 and 18, which account for about 70% of cervical cancer cases worldwide. The quadrivalent and nonavalent vaccines further protect by preventing infection with HPV genotypes 6 and 11 which cause anogenital warts. The nonavalent vaccine offers the highest level of protection by including an additional five HPV genotypes.

Enhancing Global Equity for Women and Girls

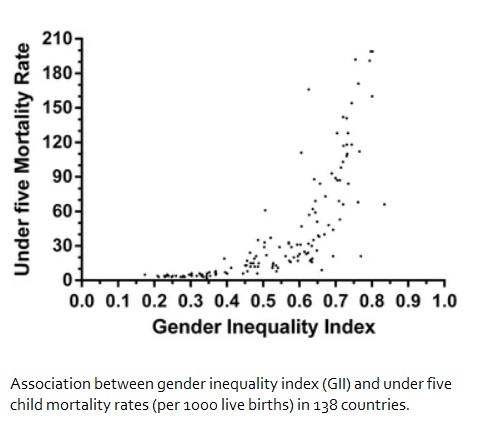

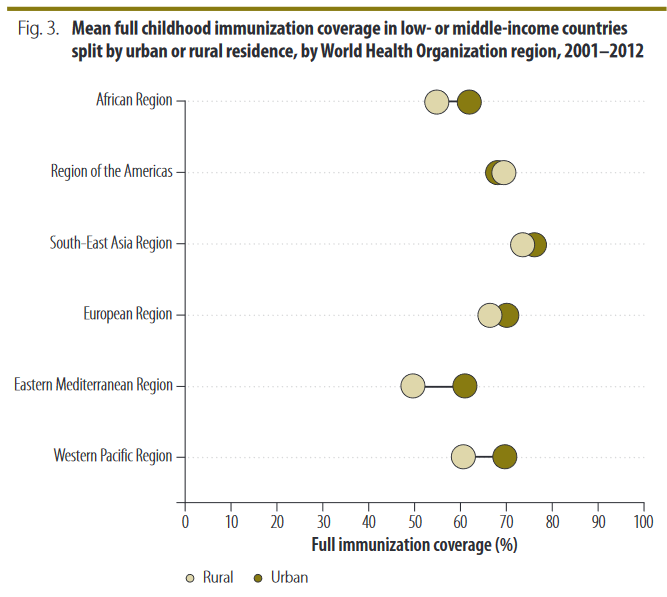

The vast majority of women and girls who have been protected by receiving an HPV vaccine are based in high-income countries, while the most vulnerable populations with the highest burden in terms of cervical cancer incidence and mortality remain largely unprotected in low-resource settings.

- Only 1% of the 118 million women and girls included in HPV vaccine programs between 2006 and 2014 were from low- or lower-middle-income countries, according to an analysis from 20164.

- High initial prices for HPV vaccines have limited access for women in low-income countries: high-income countries comprise only 14% of cervical cancer cases, but almost 70% of women receiving HPV vaccines4.

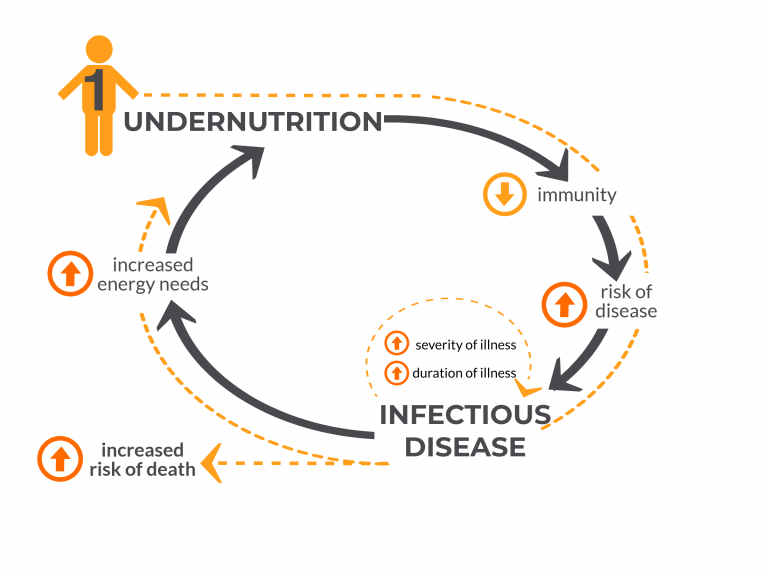

- Women from low- and middle-income countries can also face compounded health risks due to high burdens of HIV: rates of cervical cancer are estimated to be four to five times higher among women who are living with HIV compared to HIV-negative women, according to a 2016 UNAIDS report5.

Economic Impacts and Cost-Effectiveness

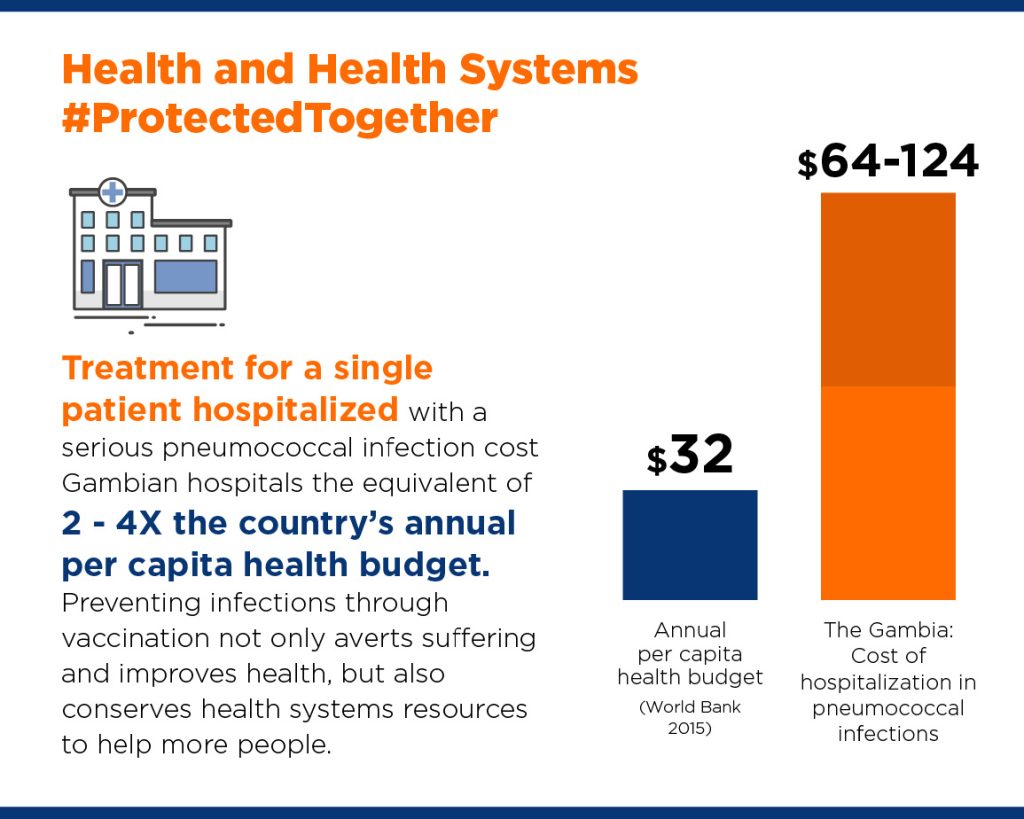

High prices have been cited as a major barrier limiting HPV vaccine access. Countries that face the greatest challenges in financing HPV vaccines often may have the most to gain from implementing these valuable vaccination programs.

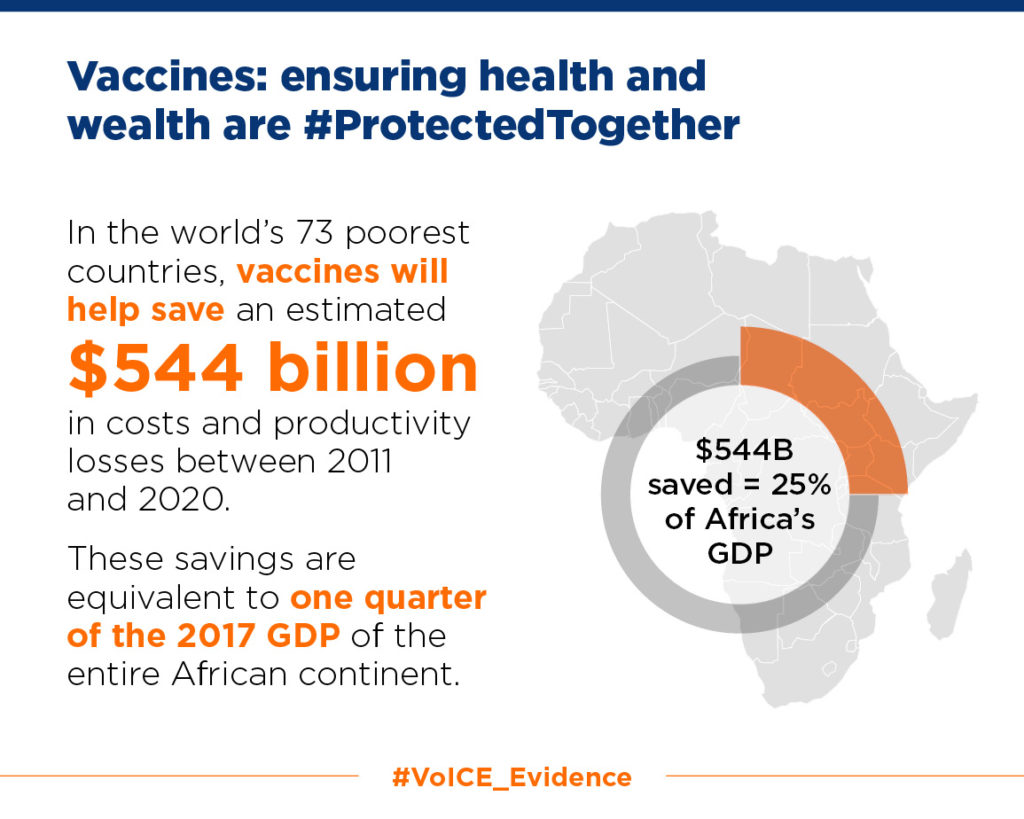

- A 2016 health economics analysis6 of return on investment for vaccines in 94 low- and middle-income countries estimated that HPV vaccines would yield a 3-fold return on investment between 2011 and 2020.

- A 2020 cost-effectiveness analysis7 using the PRIME (Papillomavirus Rapid Interface for Modelling and Economics) tool found that “HPV vaccination provides greater health benefits and is more cost-effective than was previously estimated” and recommended, “The WHO African region is expected to gain the greatest health benefits and should be prioritised for HPV vaccination.”

- A 2020 proof-of-concept health economics framework8 described how HPV vaccination could lead to increased labor participation and economic output, potentially enhancing gender equity for women. “The improvements in economic productivity from years of employment gained by female workers could be approximately $4.7 million in Tanzania, $24 million in India, and $18 million in the United Kingdom (in US$2015).”

Overcoming Low Knowledge and Awareness of HPV Vaccination

One obstacle to increased uptake of HPV vaccination in LMICs is limited public knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV, and the benefits of HPV immunization. Despite current low levels of knowledge about the HPV vaccine, several studies have reported high acceptability and a willingness among women and girls to receive the vaccine for themselves or their daughters.

- In Bangladesh, a 2018 study9 among ever-married women showed that even with low knowledge of cervical cancer or HPV vaccine, more than 90% of women were willing to receive the HPV vaccine themselves or to have their daughters receive it.

- In Mozambique, a 2018 study10 among school-aged girls found that while only 33% had heard of HPV, 91% were willing to receive the vaccine.

- In Haiti, a 2017 study11 presented similar findings from adult women over age 18. Only 27% had heard of HPV and 10% knew of the HPV vaccine but 96% were willing to vaccinate their daughters once they learned about the purpose of the vaccine.

- Several systematic reviews focused on African and Asian populations have also found that even when knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine is low, acceptability of the vaccine was often high. A 2014 systematic review12 of HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa found that across 14 unique studies, acceptability of the HPV vaccine for daughters ranged from 59–100%.

Successful HPV Vaccine Delivery Campaigns

Several key obstacles limit HPV vaccine expansion efforts including inadequate health system capacity, inconsistent vaccine supply, lack of general knowledge about the vaccines, and unique implementation challenges associated with vaccinating older children and adolescents. Innovative approaches for delivering the vaccine to girls in the target age range have shown some promise to advance HPV vaccination.

- In 2010, Bhutan13 became the first low- or middle-income country to implement a national HPV vaccination program through a school-based delivery model. This program achieved coverage between 90% and 99% in the target populations of school-aged girls.

- Rwanda’s national HPV vaccination program14 is another example of a successful school-based rollout. This school-based delivery approach was so successful that it was able to obtain 93% coverage among girls in grade six based on completion of a three-dose series.

- Despite potential gains though successful school-based vaccination programs, it is also important to ensure equitable access to HPV vaccination for girls who are not currently enrolled in or attending school. Girls who represent hard-to-reach populations may be more vulnerable and at higher risk of HPV infection and cervical cancer, particularly if they are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive15.

Meeting Unprecedented Demand

Despite cost barriers, high demand for HPV vaccines in 2018 led to a supply shortage of HPV vaccine due to, “the unprecedented uptake of HPV support in Gavi-eligible countries, combined with increased global demand for HPV vaccines from higher-income countries.”

In June 2020, Gavi announced that five manufacturers were committing to the prioritization of HPV vaccine supply to support Gavi-supported countries. This commitment will ideally increase the affordability and promote accessibility of the vaccine.

Gavi’s most recent estimate is that up to 84 million girls in the world’s poorest countries could have access to HPV vaccine over the next 5 years which would advance public health by preventing 1.4 million cases of cervical cancer deaths worldwide.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

- Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(2):e191-e203. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6

- Brisson M, Kim JJ, Canfell K, et al. Impact of HPV vaccination and cervical screening on cervical cancer elimination: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2020;395(10224):575-590. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, et al. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(7):e453-e463. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7

- HPV, HIV and Cervical Cancer: Leveraging Synergies to Save Women’s Lives. UNAIDS; 2016. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/HPV-HIV-cervical-cancer

- Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Brenzel L, Walker DG. Return On Investment From Childhood Immunization In Low- And Middle-Income Countries, 2011–20. Health Affairs. 2016;35(2):199-207. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1086

- Abbas KM, van Zandvoort K, Brisson M, Jit M. Effects of updated demography, disability weights, and cervical cancer burden on estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination impact at the global, regional, and national levels: a PRIME modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(4):e536-e544. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30022-X

- Portnoy A, Clark S, Ozawa S, Jit M. The impact of vaccination on gender equity: conceptual framework and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine case study. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1090-3

- Islam JY, Khatun F, Alam A, et al. Knowledge of cervical cancer and HPV vaccine in Bangladeshi women: a population based, cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 2018;18(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0510-7

- Bardají A, Mindu C, Augusto OJ, et al. Awareness of cervical cancer and willingness to be vaccinated against human papillomavirus in Mozambican adolescent girls. Papillomavirus Research. 2018;5:156-162. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2018.04.004

- Gichane MW, Calo WA, McCarthy SH, Walmer KA, Boggan JC, Brewer NT. Human Papillomavirus Awareness in Haiti: Preparing for a National HPV Vaccination Program. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2017;30(1):96-101. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.07.003

- Cunningham MS, Davison C, Aronson KJ. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2014;69:274-279. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.035

- Dorji T, Tshomo U, Phuntsho S, et al. Introduction of a National HPV vaccination program into Bhutan. Vaccine. 2015;33(31):3726-3730. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.078

- Binagwaho A, Wagner C, Gatera M, Karema C, Nutt C, Ngaboa F. Achieving high coverage in Rwanda’s national human papillomavirus vaccination programme. Bull World Health Org. 2012;90(8):623-628. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.097253

- Scaling-up HPV Vaccine Introduction. World Health Organization; 2016. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251909/9789241511544-eng.pdf?sequence=1