Maternal immunization is a promising strategy for protecting mothers, the developing fetus, and young infants during a particularly vulnerable time in their lives – especially in low- and middle-income countries where morbidity and mortality among women and their children is high. During pregnancy, vaccines allow antibodies from the mother to cross into the placenta, protecting moms and their babies from life-threatening illnesses.

Key Messages

- Maternal immunization is an important strategy for protecting infants and newborns in the vulnerable period before they can receive their own vaccinations.

- Providing high-value antenatal care (ANC) during pregnancy can include vaccination against diseases like influenza, pertussis, and tetanus—which can help set both mother and baby up to survive and thrive.

- Complications from vaccine-preventable infections during pregnancy and early infancy can have cascading health and economic effects on individuals, families, communities, and health systems.

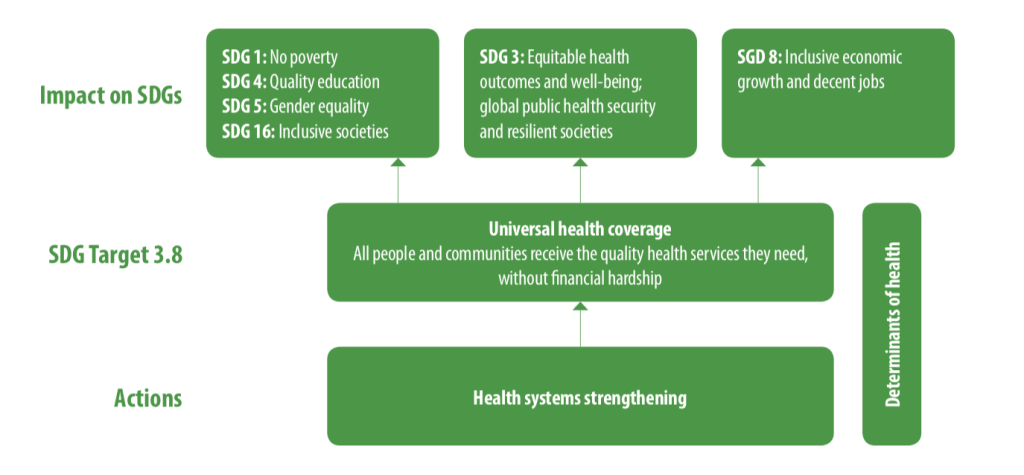

- Maternal immunization offers a critical opportunity to elevate maternal and newborn health on the broader health and development agenda and catalyze progress toward Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.

Maternal Immunization: The Window of Vulnerability

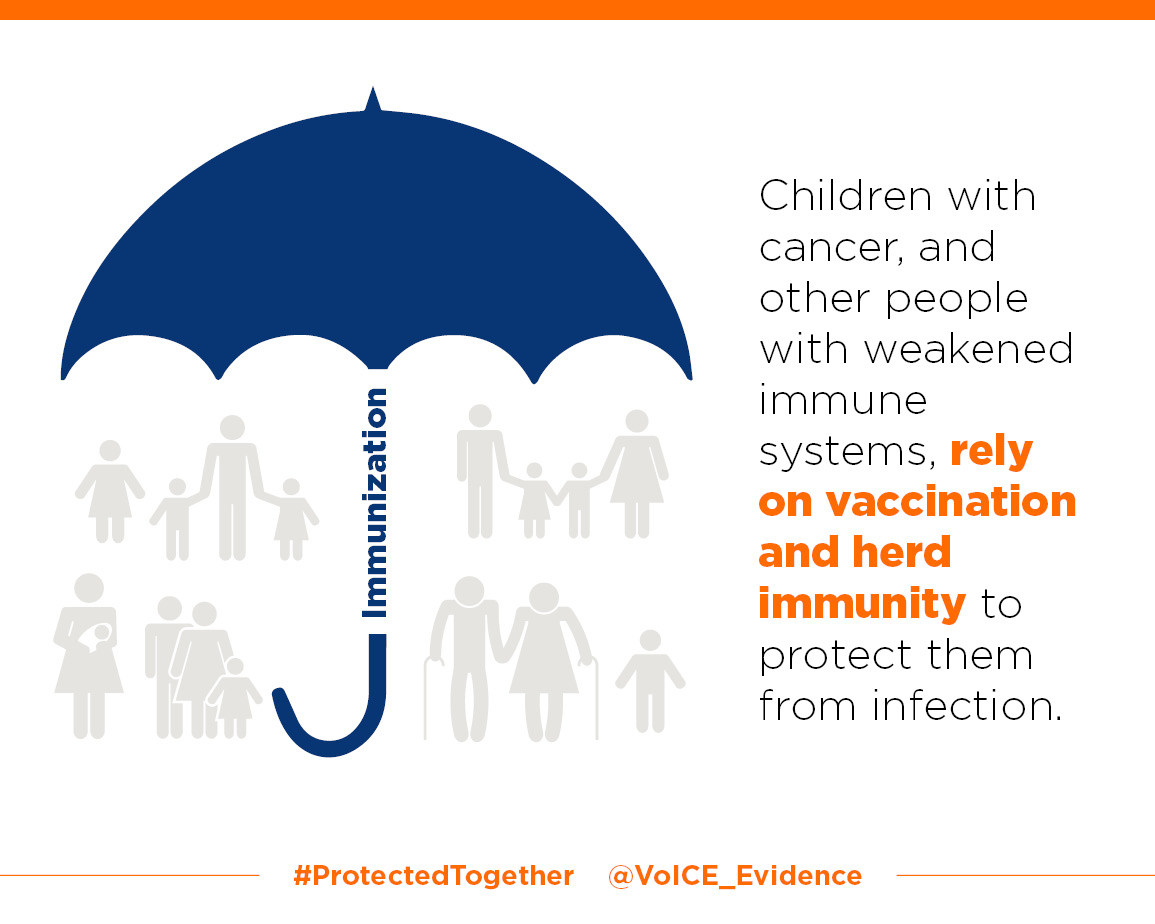

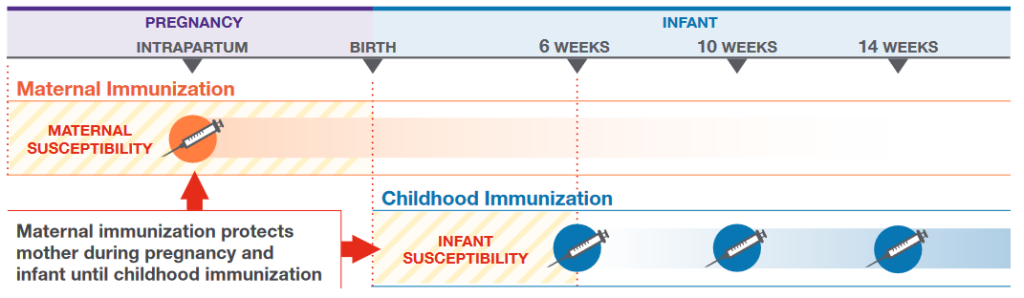

Because newborn babies are too young to receive most vaccines, they are unprotected against many pathogens that can cause severe infections leading to hospitalization, long-term health problems, or death. Maternal immunization provides an important opportunity to protect the unborn child, the newborn, and in many cases, the mother, from preventable illnesses.

Providing vaccines during pregnancy not only boosts the mother’s immunity against dangerous pathogens, but a mother’s antibodies can be passed to her unborn baby in-utero through the placenta or through breast milk. For newborn babies, these maternal antibodies provide essential protection during a “window of vulnerability” when infants are too young to get their own immunizations.

The Neonatal Period is Critical for Child Survival

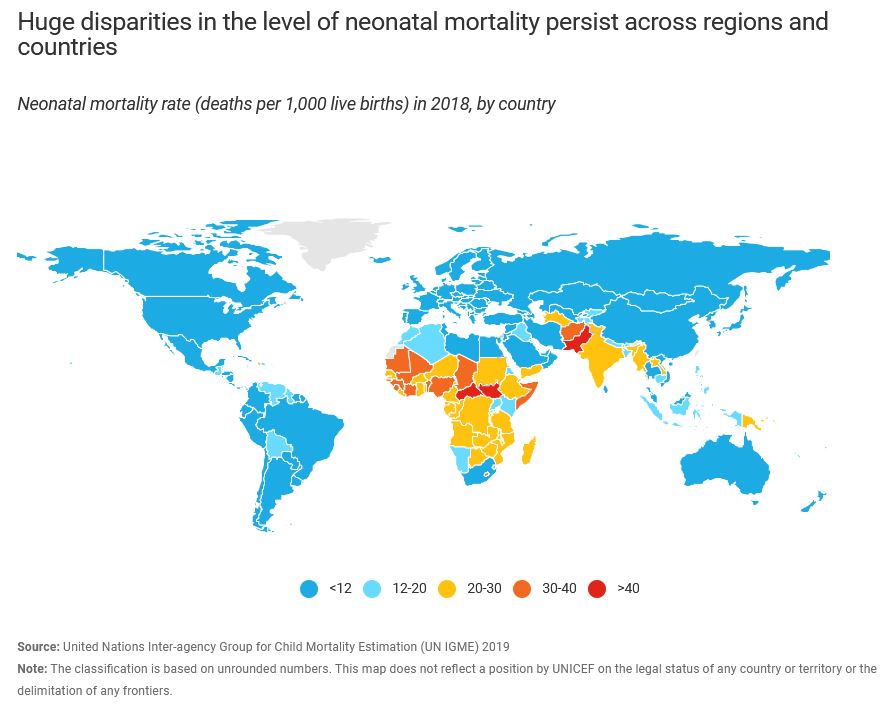

Even one preventable child death is too many. Analysis by the WHO shows that the first 28 days of life for a baby – also called the neonatal period – is when a child’s survival is most threatened. Based on 2018 estimates, around 2.5 million neonates die in their first month of life, annually around the world.

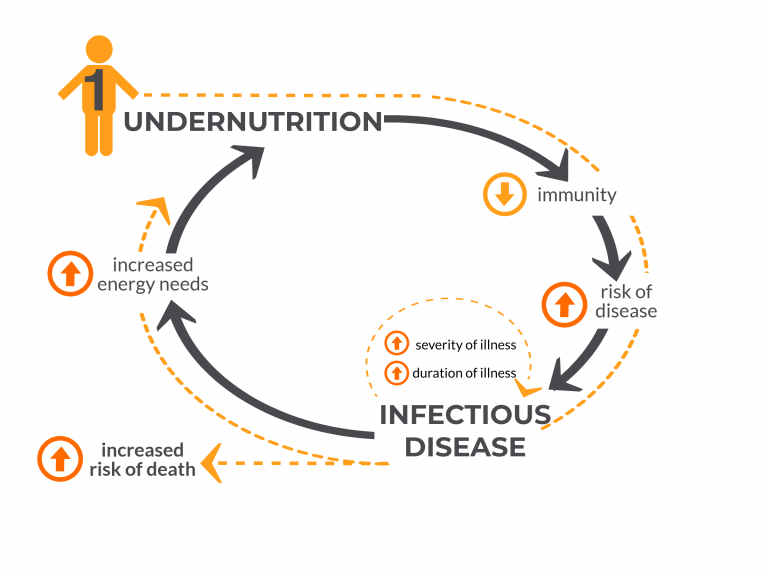

A 2015 report from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation assessed opportunities for maternal immunization in resource-limited settings, estimating that more than half of neonatal deaths in the first month of life are associated with infections (22%). When that infection is vaccine-preventable, maternal immunization can help protect mothers, the unborn fetus, and infants during this vulnerable window.

Child mortality rates have fallen dramatically, but the progress has not been even across all child ages

Maternal Immunization Can Prevent Severe, Costly Adverse Health Outcomes

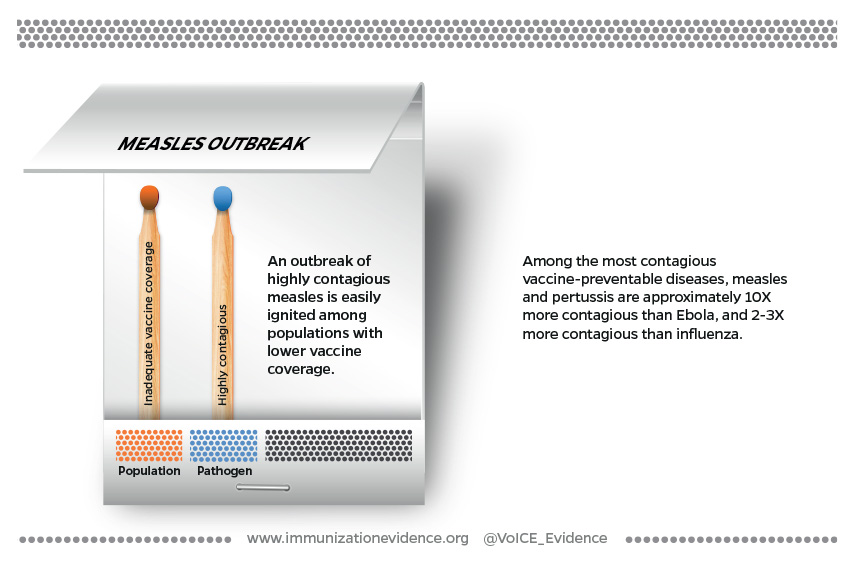

Several studies have found that pregnant women and infants under 6 months are at increased risk of severe illness from infectious diseases such as influenza and pertussis that can lead to hospitalization or admission to intensive care units.

- In a large U.S. study1, infants born to mothers who reported receiving influenza vaccination during pregnancy had an 81% lower chance of being hospitalized with influenza compared to infants whose mothers did not receive influenza immunization.

- A 2017 study2 in the U.S. found that vaccinating women with Tdap during the third trimester of pregnancy provided 81% protection against pertussis to infants <2 months and 91% protection against hospitalization for pertussis.

- A 2018 analysis3 of data from Nepal, Mali, and South Africa found evidence that maternal influenza immunization may reduce severe pneumonia episodes among infants <6 months. Overall, the incidence rate of severe pneumonia was 20% lower in infants in the maternal immunization group compared with the control group, although this rate varied by country.

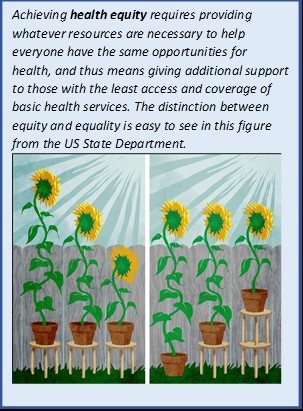

Strengthening Maternal and Child Health Equity

Globally, 2017 data show that over 800 women die every day due to preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. These deaths are inequitably distributed: the vast majority of maternal deaths (94%) occur in low-resource settings and overwhelmingly impact the poorest and most vulnerable populations, communities of women and children with the most limited access to routine health care.

Many of the same barriers that prevent women from receiving or seeking care during pregnancy and childbirth are the same barriers that prevent their children from accessing life-saving vaccinations:

- Poverty

- Distance to facilities

- Lack of information

- Inadequate and poor-quality services

- Cultural beliefs and practices

Immunization as a Gateway to Maternal Health Services

Since it was established in 1974, the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) now reaches 85% of children globally with life-saving vaccines. With its strong service delivery infrastructure, immunization can provide a gateway to help connect women and their families with additional health services. A 2019 WHO Maternal Immunization and Antenatal Care Situation Analysis (MIACSA) Project report suggests that integration of immunization with other antenatal services is a promising strategy that can lead to “increased coverage, improved system efficiency, improved user satisfaction and increased demand.”

EPI’s strong delivery system has the potential to integrate additional reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health interventions with immunization. A 2013 knowledge summary describes how with thoughtful and measured planning, non-vaccine health interventions can be integrated with immunization visits to create a “programme foundation through which broad services can be equitably provided as well as give a beneficial boost to EPI coverage.”

Mothers who Use Maternal Health Services are More Likely to Have Fully Immunized Children

UNICEF reports that an estimated 86% of pregnant women globally have some form of antenatal care contact with a skilled health provider at least once in their pregnancy. However, current WHO guidance is that women receive eight or more contacts for antenatal care over the course of a pregnancy. For many women, particularly those in LMICs, pregnancy may be the first time a woman has contact with formal health services. Several studies across different countries have found that access to maternal health services is also associated with higher rates of immunization in children.

- In Pakistan4, women who had 3 or 4 antenatal care contacts had children who were 40-60% more likely to receive all required vaccines on time compared to children whose mothers made only 1 or 2 ANC visits.

- A 2019 Nigerian study5 found that ANC attendance, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care were significantly associated with a woman’s child being fully immunized irrespective of socio-economic status, geopolitical zone, place of residence, parity, person who decides on mother’s healthcare and mother’s age. This finding is consistent with studies in Senegal, Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, and Zimbabwe, which showed that a mother’s ANC attendance was significantly associated with full immunization of her children.

- A 2019 study6 of basic vaccine coverage of children in Myanmar found that those born to mothers who received tetanus vaccination during pregnancy were three times more likely to have completed their recommended vaccinations by age two compared to children of mothers who did not receive tetanus toxoid vaccination.

The Maternal Neonatal Tetanus Elimination program has been cited as proof of concept for the feasibility and potential for maternal immunization to reduce neonatal mortality particularly in LMICs (Krishnaswamy, S., Lambach, P., & Giles, M. L., 2019)

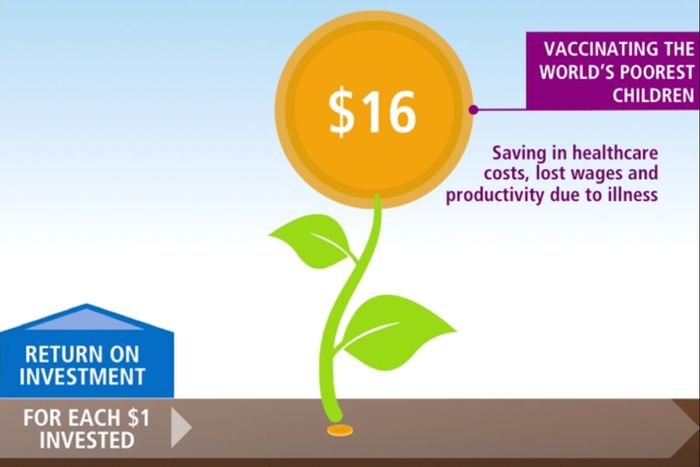

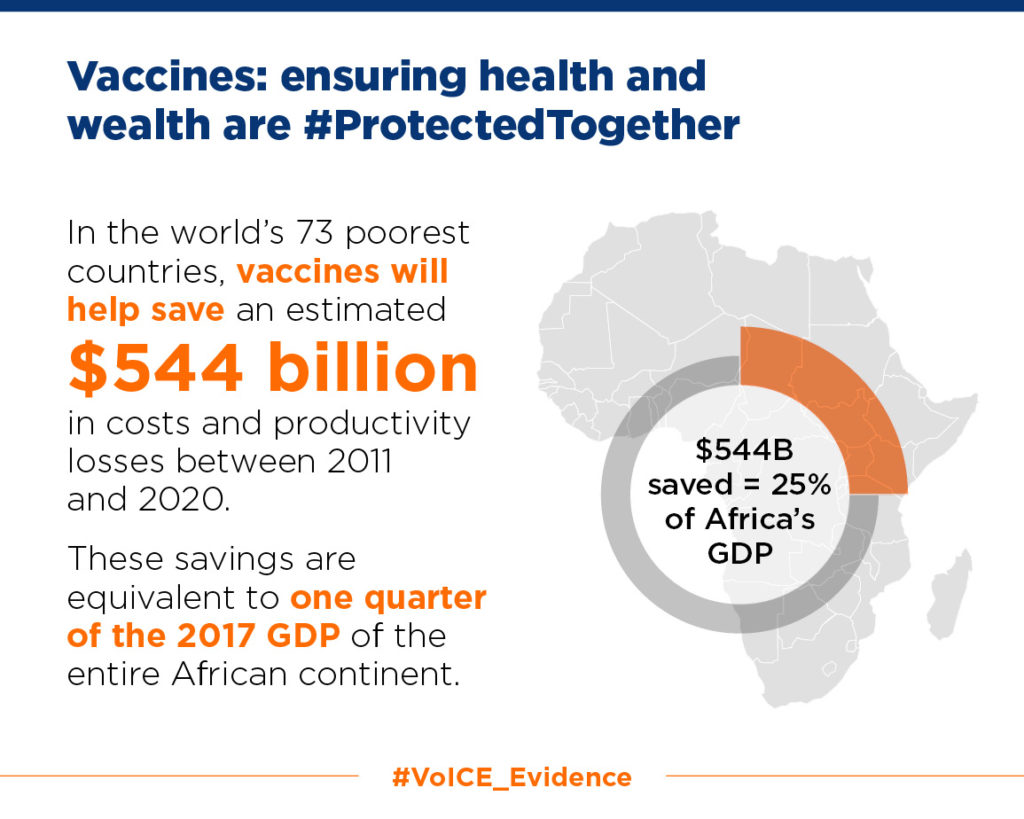

A Good Investment: Cost-effectiveness of Maternal Immunization

The cost-effectiveness of different maternal immunization strategies varies by country, context, and health priorities. Several studies examining the cost-effectiveness of maternal immunization have found that it can be cost-effective, depending on a variety of factors.

- Brazil has experienced a significant increase in pertussis incidence since 2011 which has particularly affected infants <4 months of age. A 2016 cost-effectiveness analysis7 found that introducing universal maternal vaccination with Tdap into the National Immunization Program in Brazil could be a cost-effective intervention. However, a 2020 cost-effectiveness analysis8 concluded that universal adult immunization of Tdap would not be cost-effective.

- Several analyses in high-income countries have found that maternal immunization for pertussis can be cost-effective. A 2018 study9 in Japan concluded cost-effectiveness could be reached even if only 50% of pregnant women received the vaccine. A 2016 study10 in the United States suggests that maternal immunization for pertussis is cost-effective compared to other adult vaccination strategies for preventing infection in infants too young to be vaccinated (postpartum vaccination, vaccination of a second parent, or untargeted vaccination of comparably aged adults).

- A 2016 analysis11 estimated that in Mozambique almost 18,000 neonatal tetanus cases could be prevented annually if pregnant women had better geographic access to a health facility offering tetanus toxoid vaccine. Reducing vaccine-preventable cases of neonatal tetanus could save the country an estimated $183,931,229–$522,248,480 in annual treatment costs and productivity losses.

The Future of Maternal Immunization

There are promising new maternal vaccines in development for two major causes of infant deaths that disproportionately impact those living in LMICs: Group B streptococcus (GBS) and respiratory syncytial disease (RSV).

Group B Streptococcus is a bacterial infection that causes an estimated 150,000 preventable stillbirths and infant deaths worldwide every year. A 2017 journal article12 estimates that GBS “is an important component of the worldwide burden of 2.6 million stillbirths,” accounting for an estimated 4% of stillbirths in sub-Saharan Africa. No licensed vaccines currently exist against GBS, but work is underway to develop a vaccine that can be given to pregnant women so that newborns are protected even before birth.

RSV can be deadly for infants, particularly those living in LMICs. It’s estimated that RSV causes 1.4 million hospitalizations in the first 6 months of life and 120,000 deaths before five years of age worldwide each year. Currently, the treatments available for RSV are limited but several vaccines are in development.

References

- Shakib, J. H., Korgenski, K., Presson, A. P., Sheng, X., Varner, M. W., Pavia, A. T., & Byington, C. L. (2016). Influenza in infants born to women vaccinated during pregnancy. Pediatrics, 137(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2360

- Skoff, T. H., Blain, A. E., Watt, J., Scherzinger, K., McMahon, M., Zansky, S. M., Kudish, K., Cieslak, P. R., Lewis, M., Shang, N., & Martin, S. W. (2017). Impact of the us maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination program on preventing pertussis in infants <2 months of age: A case-control evaluation. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 65(12), 1977–1983. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix724

- Omer, S. B., Clark, D. R., Aqil, A. R., Tapia, M. D., Nunes, M. C., Kozuki, N., Steinhoff, M. C., Madhi, S. A., Wairagkar, N., & for BMGF Supported Maternal Influenza Immunization Trials Investigators Group. (2018). Maternal influenza immunization and prevention of severe clinical pneumonia in young infants: Analysis of randomized controlled trials conducted in Nepal, Mali and South Africa. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 37(5), 436–440. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001914

- Noh, J.-W., Kim, Y., Akram, N., Yoo, K.-B., Park, J., Cheon, J., Kwon, Y. D., & Stekelenburg, J. (2018). Factors affecting complete and timely childhood immunization coverage in Sindh, Pakistan; A secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0206766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206766

- Anichukwu, O. I., & Asamoah, B. O. (2019). The impact of maternal health care utilisation on routine immunisation coverage of children in Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 9(6), e026324. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026324

- Nozaki, I., Hachiya, M., & Kitamura, T. (2019). Factors influencing basic vaccination coverage in Myanmar: Secondary analysis of 2015 Myanmar demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 242. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6548-0

- Sartori, A. M. C., de Soárez, P. C., Fernandes, E. G., Gryninger, L. C. F., Viscondi, J. Y. K., & Novaes, H. M. D. (2016). Cost-effectiveness analysis of universal maternal immunization with tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine in Brazil. Vaccine, 34(13), 1531–1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.026

- Fernandes, E. G., Sartori, A. M. C., de Soárez, P. C., Amaku, M., de Azevedo Neto, R. S., & Novaes, H. M. D. (2020). Cost-effectiveness analysis of universal adult immunization with tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) versus current practice in Brazil. Vaccine, 38(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.100

- Hoshi, S., Seposo, X., Okubo, I., & Kondo, M. (2018). Cost-effectiveness analysis of pertussis vaccination during pregnancy in Japan. Vaccine, 36(34), 5133–5140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.026

- Atkins, K. E., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Galvani, A. P., & Townsend, J. P. (2016). Cost-Effectiveness of Pertussis Vaccination During Pregnancy in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(12), 1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv347

- Haidari, L. A., Brown, S. T., Constenla, D., Zenkov, E., Ferguson, M., de Broucker, G., Ozawa, S., Clark, S., & Lee, B. Y. (2016). The economic value of increasing geospatial access to tetanus toxoid immunization in Mozambique. Vaccine, 34(35), 4161–4165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.065

- Seale, Anna C, Hannah Blencowe, Fiorella Bianchi-Jassir, Nicholas Embleton, Quique Bassat, Jaume Ordi, Clara Menéndez, et al. “Stillbirth with Group b Streptococcus Disease Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 65, no. suppl_2 (November 6, 2017): S125–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix585.